A Canadian Storyteller Who Helped To Define His Homeland To The World

Gordon Lightfoot 11.17.1938 - 5.1.2023

I want to be like Ralph Carter, Stompin’ Tom and Willie Nelson. Just do it for as long as humanly possible.

I didn’t quite grow up in Canada, but close enough that I developed a fondness for the Great White North. I grew up in far northern Minnesota, about an hour and a half south of the 49th parallel, the US-Canada border. It wasn’t uncommon for me to have at least one Canadian coin in my pocket; we could use them in pop machines in my hometown.

Where I grew up, winters were cold, bleak, and frozen. And if you headed up to International Falls, MN, and crossed the border into Fort Frances, ON, during the winter months, cold, bleak, and frozen was the order of many days.

We also had the International 500, a snowmobile race between Winnipeg, MB, and St. Paul, MN, that reversed course every year. So it would run north-south one year and then south-north the next. The International 500 was one of the things that helped to connect northern Minnesota with Ontario and Manitoba. For a kid from a town of less than 1000 people in far northern Minnesota, that was a BFD.

My family rarely went into Canada; there wasn’t much reason for us to drive north across the world’s largest peat bog and into the sparsely populated flatlands of southern Manitoba or western Ontario. There wasn’t anything in that corner of Canada that we couldn’t get in the US, so we stayed on our side of the border.

One thing Canada had that we didn’t was Gordon Lightfoot, whose music I can remember hearing at an early age. Much of his music spoke to the Canadian experience and the country’s history, but a lot of it was great folk music that worked well on either side of the border.

It seemed as if he’d been around forever, and when he died yesterday in Toronto, he took an era of folk music with him.

Gordon Lightfoot, the Canadian folk singer whose rich, plaintive baritone and gift for melodic songwriting made him one of the most popular recording artists of the 1970s, died on Monday night at a Toronto hospital. He was 84.

His death was announced on his official Facebook page. Other details were not immediately available.

Mr. Lightfoot, a fast-rising star in Canada in the early 1960s, broke through to international success when his friends and fellow Canadians Ian and Sylvia Tyson recorded two of his songs, “Early Morning Rain” and “For Lovin’ Me.” When Peter, Paul and Mary came out with their own versions, and Marty Robbins reached the top of the country charts with “Ribbon of Darkness,” Mr. Lightfoot’s reputation soared. Overnight, he joined the ranks of songwriters like Bob Dylan, Phil Ochs and Tom Paxton, all of whom influenced his style.

Then, in the late ‘60s and early ‘70s, the British Invasion began to overtake folk music. As a result, many well-known folk musicians and songwriters couldn’t adapt and saw their careers wane. Lightfoot was talented enough to pivot and head in a different direction.

Mr. Lightfoot began writing ballads aimed at a broader audience. He scored one hit after another, beginning in 1970 with the heartfelt “If You Could Read My Mind,” inspired by the breakup of his first marriage.

In quick succession he recorded the hits “Sundown,” “Carefree Highway,” “Rainy Day People” and “The Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald,” which he wrote after reading a Newsweek article about the sinking of an iron-ore carrier in Lake Superior in 1975, with the loss of all 29 crew members.

As a kid, I’d heard some of Lightfoot’s songs on WEBC-AM out of Duluth, MN, but I knew only that I liked the songs. I didn’t know anything about the man behind them.

It wasn’t until I went to college in St. Paul, MN, that I had opportunities to hear more of his music and become more acquainted with his story. Every year, usually (if memory serves) in late fall or early winter, Lightfoot would do a concert at Northrup Auditorium at the University of Minnesota. And so I’d get a couple of tickets and make a date night out of it with whoever I was seeing at the time.

We’d catch a bus heading north up Snelling Avenue in St. Paul, get off at University Avenue, and then transfer to a bus that would take us west on University into Minneapolis and Northrup Auditorium. It was a long trip, but for a cash-strapped college kid, it was worth it. I saw four of his concerts, and each one was a highlight of my year. Unfortunately, those were the only four of his shows I’ve ever seen, but to this day, I still remember how excited I was.

For Canadians, Mr. Lightfoot was a national hero, a homegrown star who stayed home even after achieving spectacular success in the United States and catered to his fervent fans with constant cross-country tours. His ballads on Canadian themes, like “Canadian Railroad Trilogy,” pulsated with a love for the nation’s rivers and forests, which he explored on ambitious canoe trips far into the hinterlands.

His personal style, reticent and self-effacing — he avoided interviews and flinched when confronted with praise — also went down well. “Sometimes I wonder why I’m being called an icon, because I really don’t think of myself that way,” he told The Globe and Mail in 2008. “I’m a professional musician, and I work with very professional people. It’s how we get through life.”

Gordon Meredith Lightfoot Jr. was born on Nov. 17, 1938, in Orillia, Ontario, where his father managed a dry-cleaning plant. As a boy, he sang in a church choir, performed on local radio shows and shined in singing competitions. “Man, I did the whole bit: oratorio work, Kiwanis contests, operettas, barbershop quartets,” he told Time magazine in 1968.

It was always rather odd to think of Gordon Lightfoot as only five months younger than my father, but they led very different lives, so they never felt like contemporaries to me. My father led a comparatively stable and settled life; Lightfoot’s was anything but stable or settled, not unusual for a successful musician, I suppose.

Every now and then, I’ll listen to Lightfoot’s “Canadian Railroad Trilogy,” partly because it reminds me of how similar and yet different the histories of the US and Canada are. Both countries’ coasts were united by railroads, and the sacrifices and struggles to knit East and West together were similar. Canada, however, was far more rugged and challenging to conquer.

“Canadian Railroad Trilogy” is a beautiful song, but very light in historical context. While it chronicles those who toiled to build the railroad that tied Canada together, Lightfoot omitted the racial abuses that were part and parcel of that undertaking. Neither do his lyrics address the brutality visited upon the First Nation peoples who lived on the lands appropriated for the railroad.

Of course, “Canadian Railroad Trilogy” was written to celebrate Canada’s centennial in 1967, not as a history lesson. And it wasn’t until the early 21st century that White Canadians began to recognize the need to understand what their forebears had done to minorities and First Nation peoples. Walk through the University of British Columbia Plaza in Vancouver today, and you’ll see a graphic depiction of the damage done to First Nation peoples.

Even today, Canada is a country far with far more wide open spaces than cities. Most of its population lives within less than 100 miles of the US border. Northern Canada is very lightly populated. Though its land mass is larger than the US, Canada’s population is less than 15% of the US.

Lightfoot’s music always reflected a very Canadian essence. While there were very personal aspects of his work that Americans could relate to, he was a Canadian hero because his music was relatable to Canadians. He remained in Canada, made his life there, and traveled extensively in remote parts of the country. If you listen to “Canadian Railroad Trilogy,” what you hear is a declaration of love for the country and its history. His quiet and unmistakable patriotism is impossible to miss, but he was hardly a flag-waver. Instead, he loved his homeland fiercely but quietly and was happy to call it home.

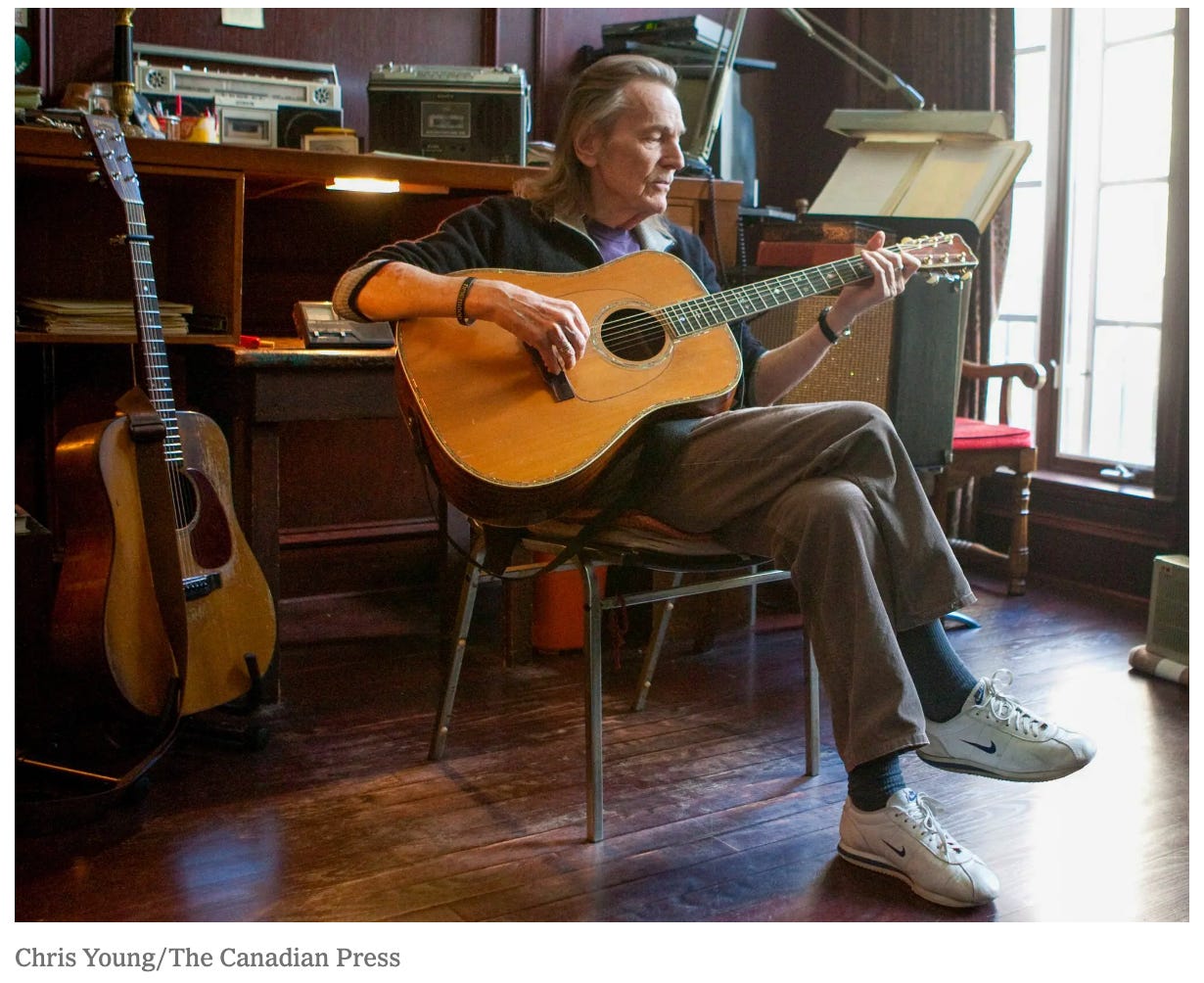

Mr. Lightfoot, accompanying himself on an acoustic 12-string guitar, in a voice that often trembled with emotion, gave spare, direct accounts of his material. He sang of loneliness, troubled relationships, the itch to roam and the majesty of the Canadian landscape. He was, as the Canadian writer Jack Batten put it, “journalist, poet, historian, humorist, short-story teller and folksy recollector of bygone days.”

He struggled on a personal level throughout his life. He married three times, had six children, wrestled with alcoholism, and found it difficult to maintain close relationships. He freely admitted that he’d paid a steep price for allowing his career to take precedence over his personal life. His obsessive work and touring schedule took a significant toll on his family and relationships.

To his credit, he was able to overcome his alcohol addiction. His third marriage to a woman 23 years his junior was his happiest. And he continued writing and performing into his 80s. He’d said he wanted to do it “for as long as humanly possible.” And, to his credit, that’s essentially what he did.

During his career, Lightfoot collected 12 Juno Awards, including one in 1970 when it was called the Gold Leaf. He was also named four times as top folk singer at the RPM Awards — the 1960s predecessor to the Junos. He was nominated for four Grammy Awards, received an Order of Canada citation in 1970 at the age of 32, and was promoted to Companion of the Order of Canada in 2003.

In 1986, he was inducted into the Canadian Recording Industry Hall of Fame, now the Canadian Music Hall of Fame. He received the Governor General’s Award in 1997 and was ushered into the Canadian Country Music Hall Of Fame in 2001.

On top of his musical accomplishments, Lightfoot branched out into acting with the 1982 Canadian film “Harry Tracy, Desperado,” starring Bruce Dern and Helen Shaver. Later in the decade, he appeared on an episode of prime-time soap “Hotel,” where he tapped into his own experience to play a musician struggling with alcoholism.

Perhaps the biggest reason for Lightfoot’s success was that he could absorb and translate stories for his audience. His 12-string guitar, subtly emotional voice, and ability to tell tales stripped of artifice made for an experience few of his contemporaries could match.

I can think of no one today who can tell a story musically with the depth of emotion and skill that Gordon Lightfoot could. He was and will forever remain one of a kind.

As a (very amateur) guitarist, I always admired Lightfoot’s ease and facility on his 12-string. It was the perfect partner to the stories he told, always understated and supportive, never the dominant force. His 12-string provided his songs with the subtle infrastructure critical to the stories he told.

I think it’s safe to say that we’ll not see anyone quite like him again, and I suspect that Canada is in mourning much as the US will be on that sad and inevitable day when Willie Nelson sheds his mortal coil.

If you have the opportunity today, raise a glass to Gordon Lightfoot. He was a hero to Canadians, but he also significantly impacted those of us who grew up in the northern tier of the US. Our world is poorer for his departure from it.