They say that without a full armory of heat panels, space rockets would burn to cinders upon reentry to Earth’s atmosphere. I’m like that when I reenter the United States, except that my heat panels consistently fail me. I think I’m ready, but I’m not. First comes the oppression, then the dismay, then the horror. Being in Texas amplifies these emotions tenfold. How do we Americans maintain this breakneck pace? How do we survive? How did we make a virtue out of being overworked, over-leveraged, and overwhelmed?….

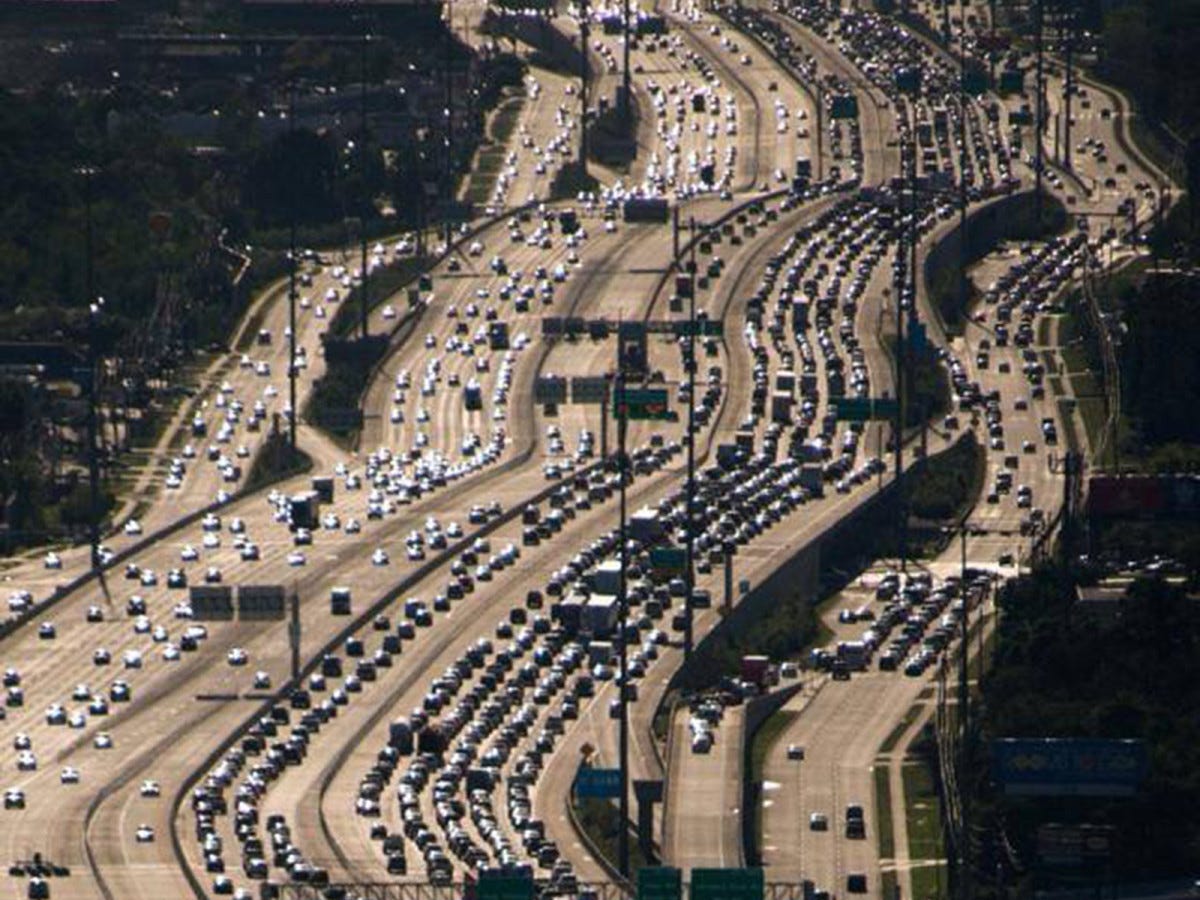

Much of the U.S., Houston especially, is so unnecessarily ugly. We sacrifice everything—our history, our culture, the things we see everyday whose hideousness affects us whether we realize it or not—to the gods of consumerism and convenience. Major cities seem to be in a heated competition to shed previous iterations of themselves in a never-ending cycle of build and destroy, build and destroy.

Over the past couple of weeks, I’ve been closely following American expatriate writer Stacey Eskelin as she traveled from her home in Italy to visit friends and family in Houston. After having been prevented from traveling home for the past three years, mostly because of the COVID-19 pandemic, I found her perspective on Houston, where I lived for ten years, and America to be fascinating. And somewhat disturbing.

Despite what many may think, America isn’t God’s own country. We’re not the Paradise on Earth that many America Firsters believe us to be. I say that not as a value judgment, but merely as the opinion of one person who’s seen the world outside our borders. Trust me, we don’t always measure up as well as we’d like to think.

Houston, like so much of this country, IS unnecessarily ugly. Too big, too hot, too humid, too full of itself, and too unwilling to recognize the race-based inequality that’s a reality of day-to-day life in the Bayou City, Houston is the closest thing to Hell America has to offer. But that’s just my opinion of one man, and I’m not an objective observer. I’ve seen Houston at its worst- after Hurricane Ike in 2008- but I can’t say that I’ve seen it at its best, whatever that might be.

America, wonderful in many ways though it may be, is not a place that fosters a pace of life conducive to good mental health and rewarding interpersonal relationships. In fact, this country has become a place where it’s surprisingly easy to become terribly lonely in the middle of a throng of people. And the worst part is that while we live in a prison of our own creation, we have the keys that would allow us to escape. We simply choose to not use them.

Most Americans wake up, drive to work alone in cars, put on a brave, false front at their place of employment (perhaps the most isolating thing of all), and then drive back alone. If they have kids, those kids are likely addicted to their smartphones. In 2021, people checked their smartphones 58 times per day. Eighty-eight percent of Americans are now “zombie eaters,” who stare at some kind of screen while eating. We’ve become a nation afflicted by digital autism. No one interacts anymore—not meaningfully, at least. We swipe right on Tinder and Bumble, we order off screens, we consume porn on screens, we shop on screens, and we rarely bother going to malls anymore. I can’t tell you how many people I saw, especially young people, wandering blindly and aimlessly with a screen in front of their faces. What’s real anymore? What’s virtual?

In one way or another, we are desperately trying to escape the menace of American life. We’re lonely and searching, well-versed in the ways of technology, perhaps, but unable to interact face to face. Here in Europe, you sit at cafés and chat with passersby, people you see every day. Folks know you at the supermarket. They say hi to you on the street. These micro-interactions are important [.]

Time was when American homes were built with front porches. People sat on those porches and interacted with neighbors and friends who happened to pass by. It was how many people caught up on what was happening around them. Then along came the suburbs with homes built more like fortresses on cul-de-sacs that meant the only people who went there were the people who lived there. We became self-contained entities, isolated even from our neighbors, together and yet very isolated from one another.

(And that’s for the declining numbers of Americans who can even afford to purchase a home these days. With the median price of homes in many cities approaching (or exceeding) $1 million, too many Americans have been priced out of the housing market and are condemned to being permanent renters.)

Today we rarely take the time- or rarely have the time- to sit in our front yards (our houses no longer have porches) and talk to friends and neighbors as they pass by. For one, few people walk anymore, and two, when they do go anywhere, it’s invariably safely ensconced within the steel and glass confines of an automobile. This is particularly true in Houston, where life without an automobile is virtually impossible.

The pandemic has created a world in which even when we do interact with others, odds are that it’s over Zoom or a similar teleconferencing application. People have learned how to work and be productive in their own homes without human interaction. With the pandemic now entering a less threatening period, many are resisting having to go back to their offices, and many who previously occupied an office cubicle are quitting because they don’t want to go back.

That isolation and loneliness and the frantic, insane pace were like a scream I heard everywhere I went in the U.S. God, it’s lonely there, even if you have friends and family. Isolation is a uniquely American disease. We’ve innovated and “convenienced” ourselves into our own little hermit kingdoms, first with cars, then with air conditioning, and now with our individual online realities. We turn over every virtual rock, looking for our acres of diamonds, without realizing they were beneath our feet the whole time. The curated lives we create for ourselves on social media are fake. That, too, contributes to our feeling of isolation; not only from others, but more importantly from our own authentic selves.

It’s not going to end well, this screen dependence and the isolation, Balkanization, and depression it breeds. Let’s face it: we’re addicted. A nation of addicts doesn’t just drift apart; its flies apart. And that’s exactly what’s happening. Isolation is sustainable only for so long. Before you know it, life is nothing but a raw Darwinian struggle, a fight for survival.

We’ve forgotten, if we ever really acknowledged, that human beings are social animals. We might like to think that we can function on our own, but the truth is that we need human interaction, if for no other reason than to maintain sanity. Sure, we can exist as individuals in our separate fiefdoms, but we can only really LIVE together, where we can laugh, love, and commiserate. There are times when we need the support of others, and yet we’ve so thoroughly walled ourselves off that we believe we no longer need it.

We do that at our own peril, and it shows in the Balkanization of American politics and social interaction. America has become a place where disagreements are no longer excuses for spirited discussion, but rather reasons to smite those not enlightened enough to think, live, love, and believe as you do.

One of the biggest problems Americans have is a loss of perspective. Very few of my compatriots have had the experience of living or traveling overseas. This means that they’ve never been exposed to other cultures and other ways of looking at life. They see America and American culture as the be-all and end-all because it’s all they know.

I’ve been fortunate enough to have had the opportunity to live overseas twice- in Cyprus and in Croatia and Kosovo. One was a war zone and the other not so far removed from being one, which presented its own unique challenges, but I learned to live and enjoy life at a slower pace. I came to understand the power of human connections and interaction. And I thoroughly enjoyed being in a place where people took the time to enjoy life instead of racing to be somewhere.

Sure, there were drawbacks. I couldn’t go to a grocery store and have my choice of 15 brands of cereal. I didn’t have access to the plethora of foods and consumer goods I was used to in America. Schedules were so flexible as to frequently be meaningless. But once I learned that I could get by without the things I’d once viewed as “essential,” life became very enjoyable. I began to slow down and I appreciated the people around me more- because I felt as if I could take the time to experience them without having to worry about being late for my next commitment.

Sure, life in a Third World country often isn’t “convenient,” at least not the way we as Americans define it. Then again, once I adapted to that lack of convenience I began to realize that it didn’t detract from my quality of life. I found that once I changed my expectations and learned to slow down, life was good. My calendar wasn’t full from sunup to sundown. I didn’t have to juggle commitments. And I didn’t have people nipping at my heels, wondering when things were going to get done.

I also wasn’t stuck in airports, fighting traffic, or losing time to things I had no control over. I learned to accept inefficiency and ineptitude as the cost of being in a country where things happened at a slower pace. Sure, it was frustrating at times, but learning to live with that was part of the deal.

I’m not going to predict what the future holds for America. I’m not a social scientist, just an observer of the human condition concerned about what he sees. And I AM concerned. There are so many things Americans could learn from the rest of the world, but collectively we’re too arrogant to believe that anyone outside our borders has anything worthwhile to teach us. And so we continue down a path that may well continue to prove that if we don’t hang together we just might hang separately.

I miss the days when dinner started at 9 pm and meant leisurely dining and conversing for three or four hours. I miss front porches. I miss talking to neighbors. I miss the social networking that living in a foreign country inevitably creates. There’s so much that we could learn in this country, but that would mean slowing down, pulling our faces out of our screens, and experiencing the world around us.

I fear we’re too far down that road and too thoroughly addicted to be able to turn back now. What that means for our future is anyone’s guess- but I’d wager that it’s not good.

Thank you for taking the time to read this. If you enjoyed it, I hope you’ll take a few seconds and join the party via a paid subscription. While you’re at it, why not forward this to a few like-minded friends who might also enjoy it!! You can also donate via Venmo (@Jack-Cluth).

I love what you wrote here--and I think you're eerily astute about the problem. Loneliness is America's disease. It's everywhere, all at once, so omnipresent most Americans don't even know it's there. Part of that loneliness stems from our inability to respect and honor the past. We're always fleeing from it. And that just makes us all the more desperate to forget who we really are and lean into the ultimate con: the promise of future fulfillment. When we win the lottery, when we get that house, when we get a promotion, when we finally have an IRA. We're so busy looking forward, we have no idea where we've come from and how it has affected us.