In the United States, the phenomenon dubbed as the “Great Resignation” seems to be picking up speed. A record 4.3 million U.S. workers quit their jobs in August, according to new data from the Labor Department — a figure that expands to 20 million if measured back to April. Many of these resignations took place in the retail and hospitality sectors, with employees opting out of difficult, low-wage jobs. But the quitting spans a broad spectrum of the American workforce, as the toll of the pandemic — and the tortuous path to recovery — keeps fueling what Atlantic writer Derek Thompson has described as “a centrifugal moment in American economic history.”….

“This [pandemic] has been going on for so long, it’s affecting people mentally, physically,” Danny Nelms, president of the Work Institute, a consulting firm, told the Wall Street Journal. “All those things are continuing to make people be reflective of their life and career and their jobs. Add to that over 10 million openings, and if I want to go do something different, it’s not terribly hard to do.”

One of the phrases we kept hearing in the aftermath of the attacks on the World Trade, the Pentagon, and in Shanksville, PA, was that “9/11 changed everything.” And in many ways, it did. Until just a couple of months ago, America had been at war for just shy of 20 years. As a result, Americans became less trusting of those who didn’t look, act, or believe as they do. They feared “The Other.” As a result, America and Americans have changed fundamentally, in ways that would prove profoundly tricky to undo.

The COVID-19 pandemic has also “changed everything.” It’s reshaped our culture, politics, and economy. It’s wreaked havoc with global supply chains, making it more difficult (and more expensive) to get day-to-day products whose availability we’ve never previously questioned.

The pandemic has also fundamentally changed the relationship millions of Americans have with their careers. The nature of work and how we think of it has changed for millions. In 2020, homes became offices and, in some cases, schools. “Zoom call” became a ubiquitous phrase many of us are sick to death of and would love to sentence to a horrible, painful death.

The enforced downtime created by the pandemic set many on the path of reconsidering not only their career but their entire life in some cases. The fundamental question of “Why?” took on new meaning. Do we work to live, or live to work? Why do we allow our careers to assume such dominant, even tyrannical roles in our lives? Are there better ways to meet our obligations and provide for those who depend on us?

After all, how many people ever said, “I wish I’d spent more time at the office” when they're hooked up to a ventilator and taking their last labored breaths in a COVID-19 ward?

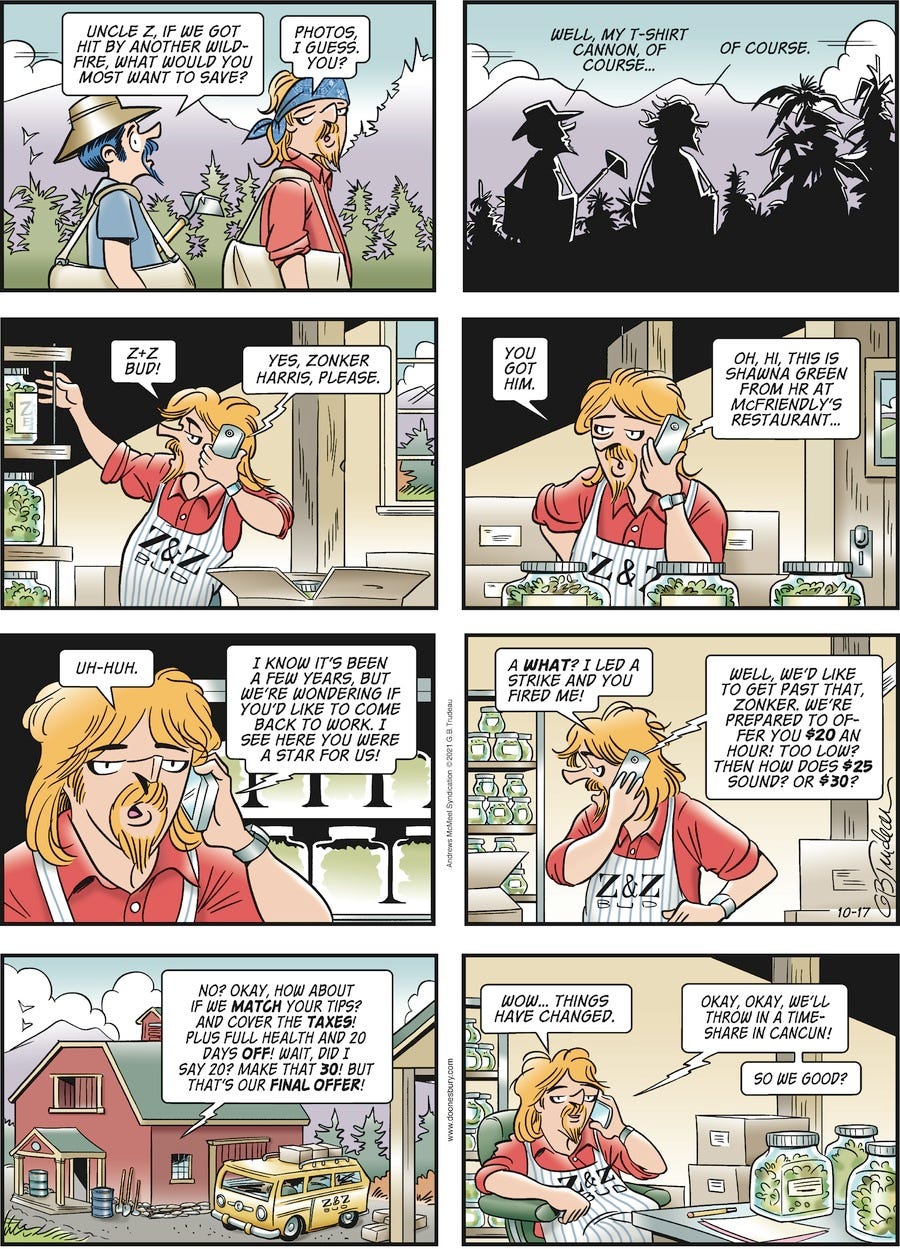

Millions of people have decided that they no longer want to fritter away their lives toiling at thankless, demanding, and low-paying jobs. It’s one of the biggest reasons the restaurant industry is struggling to find workers. After being away for months and seeing what their life can be without the abuse, long hours, and low pay, many restaurant workers have decided that enough is too much.

Part of the problem is that too many employers have yet to awaken to the reality of the new economic world we’re inhabiting. It’s no longer a buyer’s market where they can pick employees and dictate compensation and working conditions. Instead, the past 20 months have shown workers that, even as individuals, they possess leverage they can maximize.

Employers may continue to decry a “labor shortage” if it suits their purpose. They may insist on flogging their view that “people just don’t want to work anymore.” Truthfully, they’d do well to remove their anteriors from their posteriors and see the world as it is. Reality has passed them by, and they’re no longer in the power position they were prior to the pandemic. The labor market in mid-October 2021 and the collective attitude toward work look nothing like they did in March 2020.

I’m not at all sure that’s a bad thing. One of the problems with employers in America is their profound collective sense of arrogance and entitlement. For too long now, they’ve acted as if they’re God’s gift to the American economy, and that workers should be groveling at their feet.

The truth, of course, is somewhat different. Over the past 20 months, workers have had an enforced opportunity to take stock of their situations…and many haven’t liked what they saw. Instead, they see employers treating workers like interchangeable parts- low pay, awful working conditions, almost zero incentive to excel- and they wonder why? Why continue working like draught horses to line their employer’s pockets when none of the benefits trickle down to them? Why work 40+ hours a week with little chance of advancement or significant pay increases? Why continue working in environments in which they know they’ll be treated like chattel?

Why, indeed?

All work is honorable, though all work isn’t compensated honorably or even comparably. Perhaps the biggest problem with our economy lies in its compensation structure. Frontline workers, the ones doing the heavy lifting (and those primarily responsible for a company’s success or failure) are uniformly among the most poorly compensated. Meanwhile, senior executives in penthouse suites who haven’t lifted anything heavier than a cell phone in years, make hundreds (sometimes thousands) of times more than their frontline employees.

There’s no way to sugarcoat that this is a terrible business practice. It continues because it enriches a fortunate few at the expense of the many at the bottom of the corporate food chain. You can do this when you don’t respect your employees and view them as infinitely replaceable resources.

Fortunately, there are reasons for encouragement, and one of the silver linings can be found within the pandemic.

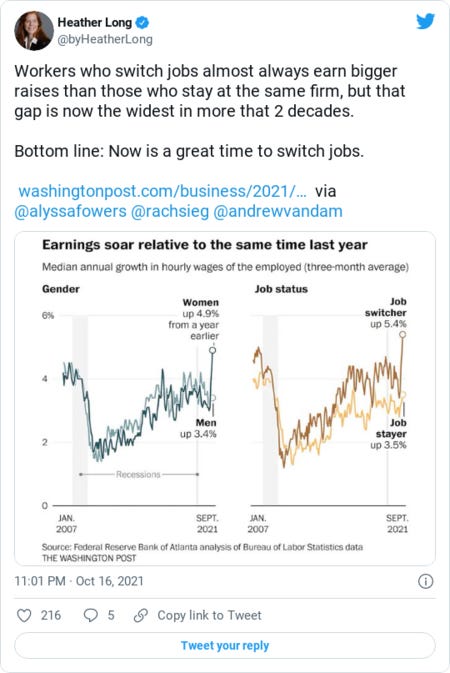

“The truth is people in the 1960s and ’70s quit their jobs more often than they have in the past 20 years, and the economy was better off for it,” wrote Thompson in the Atlantic. “Since the 1980s, Americans have quit less, and many have clung to crappy jobs for fear that the safety net wouldn’t support them while they looked for a new one. But Americans seem to be done with sticking it out. And they’re being rewarded for their lack of patience: Wages for low-income workers are rising at their fastest rate since the Great Recession.”

One thing the pandemic has forced millions of workers to do is to become more tech-savvy. I suspect most of us have spent far more time staring at computer screens over the past 20 months than we’d ever thought possible. Companies have learned that physical offices are often no longer necessary. If you have a laptop and a Wi-Fi connection, it’s possible for some folks to work from virtually anywhere.

COVID-19 has forced businesses AND workers to adapt in wonderful, unexpected, and/or occasionally painful ways. It’s changed the calculus employers have relied on for so long, and it’s allowed workers to realize that they can control their work lives far more than they have previously.

The “labor shortage” employers and Republicans have decried is nothing of the sort. It’s just shorter and more convenient than saying “shortage of people who are willing to subject themselves to being mistreated and disrespected in dead-end, low-wage jobs.”

American workers now have the means and the ability to exercise more control over their careers. And they deserve to be able to do so. They don’t exist merely to pad the bank accounts of the oligarchy. They deserve to be able to create the lives they want for themselves and their loved ones.

Calling this movement “The Great Resignation” misses the point of the dissatisfaction and anger behind it. It also neglects the fundamental changes in the economy and our collective relationship to work, something I think has been long overdue. The COVID-19 pandemic has changed America, Americans, and how we define what’s truly important.

Over the long haul, that promises to make the American and world economy more diverse and purposeful. I believe it will also help Americans maintain a higher level of happiness and satisfaction in their lives and careers.

Then again, I’m a history major, not an economist, so feel free to take my observations and predictions with a large grain of salt. That said, this stuff isn’t rocket science, and it stands to reason that a happier and more satisfied workforce will be more dynamic and productive.

Aren’t revolutions’ great?

Thank you for taking the time to read this. If you enjoyed it, why not help me spread the word by passing it along to a friend or six who might similarly enjoy it. If you REALLY enjoyed it, please consider a paid subscription. Or perhaps donating via Venmo (@Jack-Cluth). It will help keep me out of trouble. :-)