Losing My Father- Reflecting On Apples And Trees

My complicated relationship with my late father

I lost my father two years ago tomorrow- July 23, 2020. The moment I learned of his passing stands out because of its comical nature. It was about noon, and I was standing naked in front of the bathroom mirror with shaving cream on my head. When the phone rang, I looked at the caller ID and saw my youngest brother’s name. I immediately knew why he was calling. First, he never calls me during the middle of the day. Second, he never calls me.

Before I even picked up the phone, I knew my father was dead. Even if I hadn’t figured it out, the despair in Patrick’s voice would’ve alerted me. He and Dad were very close, and the news of his death hit him hard. I was shocked but not particularly surprised. Dad’s frailty had been progressing rapidly.

Patrick and I spoke for a few minutes, and I promised to make arrangements to be there the next day. After hanging up the phone, I began to think about what I was feeling and realized I had no idea how or even what I was supposed to feel. My father had just died, yet I felt strangely unmoved. I was sad because I knew Dad was gone, but mostly I was unsure what to feel.

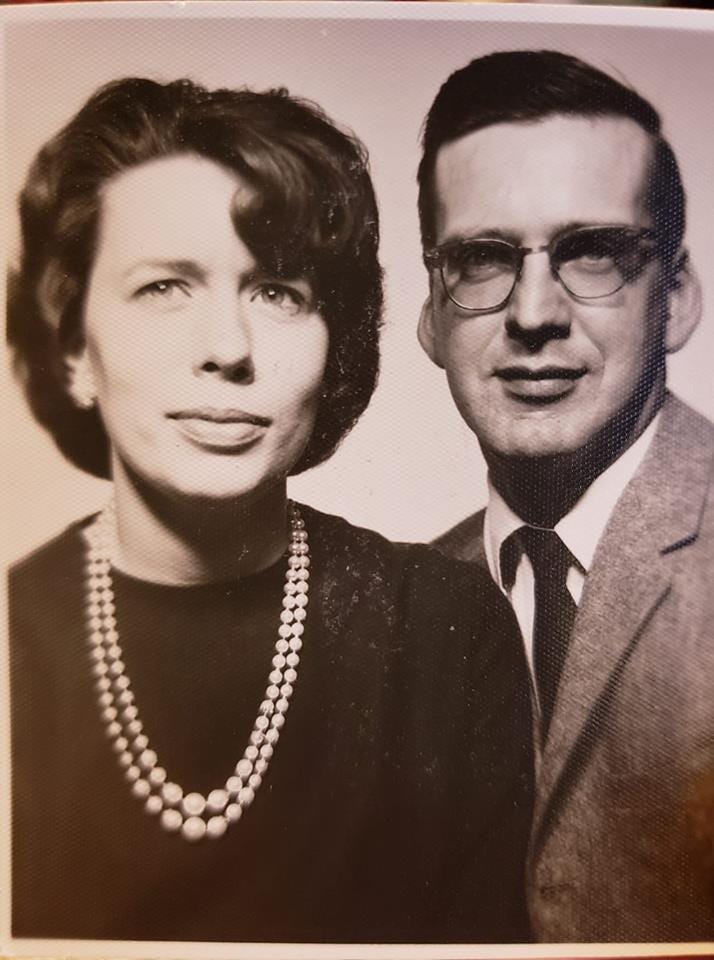

More than anything, I felt awful for my mother. She left home at 18, married my father three days later, and I came along ten months after that. They’d recently celebrated their 61st wedding anniversary. Now, for the first time in her life, she was alone at the age of 79.

I realized that I would also, at some point, have to come to grips with my feelings about my father, which were, to put it mildly, complicated. I was the firstborn of four sons. Mom was 19, Dad 22. Neither of them had much of a clue about being a parent, but they figured things out as they went along. By the time Mom was 24, she’d had the last of her four sons.

Being the firstborn in my family was no easy task. I HATED being the guinea pig for everything rite of passage. Everything was more challenging and more complicated for me, and I resented it. For example, when I got my driver’s license at 16, I wasn’t allowed to drive by myself for six months. Mark, who was a year younger, got his almost 12 months later and was allowed to drive alone within three weeks.

The fact that I’m relaying this story demonstrates how much I resented it. And there were many more instances of such perceived inequities. From my perspective, I was getting shafted. I was too self-centered to understand that Mom and Dad were making it up as they went, and everything they did with me was the first time.

That wasn’t even the worst of it, though. Dad and I never saw eye-to-eye. On anything. If he said something was white, I KNEW that whatever we were arguing about was black. It may well have been white, and I may have even known it was white, but I wasn’t about to give him the satisfaction of even the slightest of victories.

Dad demanded complete and immediate obedience. I wasn’t disobedient (most of the time), but I wanted to under the “why” behind something he’d told me to do. In most circumstances, he was in no frame of mind to explain things, and he took my inquisitiveness as rebellion. When he said, “Jump!” the only answer he expected was, “How high?” Not “Why am I supposed to accomplish by jumping?”

I wanted to understand the reason behind things, and I never accepted the concept of blind obedience. Eventually, I didn’t do well with the idea of obedience. It all seemed so pointless. Why was I expected to do things I saw no sense in doing? All I wanted was answers; all my Dad wanted to do was beat me.

Sometimes, Dad resorted to beating me with a leather belt. I’ll spare my reader the details, other than to say it took me four decades to forgive my father for the physical abuse he inflicted upon me. The sound of a leather belt being pulled out of belt loops still takes me back to the days when Dad would tell me to drop trou and bend over a chair. The beating would leave my ass red and sore, and whatever lesson he was trying to reinforce would remain unlearned. More than anything, those beatings taught me to resent him.

There’s no way I can do justice to the details of my relationship with my father in 2000 words or less, but after I left home, there was a 20-year period during which I had no contact with my family. During that time, my father suffered a stroke at age 53, which left him unable to speak, save for a few short bursts of words here and there. His mind was still sharp, but the stroke severed the connection between his brain and tongue. Over the next 29 years, my mother became his go-between with the world, and their partnership worked quite well. Dad managed to do what he could, which mostly involved working around the yard, and Mom looked out for him as best she could.

Dad’s routine was to putter around their couple of acres in the morning and return to the house for lunch around noon. Mom never really knew what he did, but she knew it kept him grounded and happy, so she never had cause to worry about him.

Then, one warm July day, Dad didn’t come back to the house for lunch. So after waiting for a few minutes, Mom set out to find him. She doesn’t move well or very quickly, but when Dad didn’t respond to her calls, she set off down the hill towards the creek at the bottom of their property to find him.

After slowly and carefully descending the incline toward the creek, Mom found Dad face-down near a tree that had recently been felled. She immediately knew he was gone, so she laboriously returned to the house, called 911, and then called my brother Patrick. Just a couple of minutes later, I got the news and began making arrangements to travel to Wisconsin.

When Erin and I decided to get married, I decided it was time to bury the hatchet (more for her than me), and we went back to Wisconsin to meet the family. To this day, I think they like her more than me. I can’t say I blame them. :-)

Since my father was no longer able to speak, it was up to me to accept my father for who he was and let the past go. Of course, I couldn’t easily forget that we'd spent 18 years at war with one another, but hanging onto that anger certainly wouldn’t do me any good.

I saw him a few times after the wedding, and we got along well enough. I could tell him that I loved him, and he could say “I love you” in return. With his limitations, that was about the best I could expect, so I learned to accept it. It was what he could do, and that became enough.

The last time I saw him, he noticed that I’d put on a few pounds. He laughed and patted my stomach. Yeah, I told him, I know.

I’d hated my father for years…and also loved him. I knew he was angry with me too, and he’s not a man given to letting go of things. Both of us could be ridiculously stubborn; yes, I know from whom I got it. In that respect, the apple didn’t fall far from the tree.

As I watched my father age and his health diminish, I often wondered if he had any regrets about what he’d done to me over the years. As the oldest, I took the heat for my younger brothers. They saw what I was going through and decided they wanted no part of it, so they knuckled under and gave in to my father. I wasn’t passive (or perhaps intelligent) enough to go along to get along. I wanted to establish my identity, and I wasn’t about to let my father beat it out of me.

That conflict is one of the biggest reasons I began writing to colleges in seventh grade. I didn’t know what to do or how to pay for it, but I was going to college and getting out of Walker, MN. I wanted to be as far away from my father as possible. And I wasn’t about to enlist in the military like my parents wanted me to.

My father is the #1 reason I’ve never had children. I swore to myself that I’d never bring a child into the world because I could never take a chance on doing to a child what my father did to me. I understand that I could’ve broken the cycle, but I don’t regret my decision, nor do I blame Dad for it. It was my decision, and I made it. I’ve taken responsibility for it, and I have no remorse, especially since I’ve done things I never would’ve been able to do if I’d had a family.

Life is about choices and consequences, no?

I have every reason to carry anger and bitterness, but I did that for far too long. It kept me from my family for 20 years. I can’t go back and replace that lost time, but I’m getting to know my family again, which feels good. I’ve gotten to know my mother in a way I couldn’t before Dad died, and I’ve re-established a relationship with two of my three brothers. I’m on speaking terms with the third, but we live in very different worlds. I enjoy his company when I see him, which is rare, but I sometimes wonder what we have in common besides biology.

Mom is now living a few doors down from my youngest brother and his wife in southeastern Minnesota, and I try to go back every couple of months. Living two time zones away on the West Coast is difficult, but I bought Mom an iPhone and an iPad after Dad died, and she’s slowly figuring out how to use them. It makes keeping in touch much easier than it used to be.

I miss Dad. Even though we were never close, I know he loved me in his way. He was my father. Losing him has changed me in ways I’m only now beginning to understand. I’ve learned that losing a parent leaves a hole nothing and no one can fill. That void will always be there.

Dad was never the sort of father I could call because I wanted or needed to talk. I never relied on him for advice. He rarely came to my games or activities when I was in high school; when he did, he was never particularly interested. Nothing I ever did seemed worthy of accolades or approval from him. He never opposed me pursuing the activities I was passionate about, but he was somewhat ambivalent, even when I was successful.

I would’ve loved to talk to him and ask why he seemed so disinterested in my activities and disappointed in me. Unfortunately, since he couldn’t speak during the last 29 years of his life, there was no way for us to have that conversation, so I had to accept what he could offer. It didn’t seem like much at times, but it was what he could do.

He’s gone now, and those answers are gone with him. So all I have now is the present, and right now, that doesn’t look too bad, so I think I’ll focus on enjoying what I have.

I love you, Dad.