To love. To be loved. To never forget your own insignificance. To never get used to the unspeakable violence and the vulgar disparity of life around you. To seek joy in the saddest places. To pursue beauty to its lair. To never simplify what is complicated or complicate what is simple. To respect strength, never power. Above all, to watch. To try and understand. To never look away. And never, never to forget.

Arundhati Roy, The Cost of Living

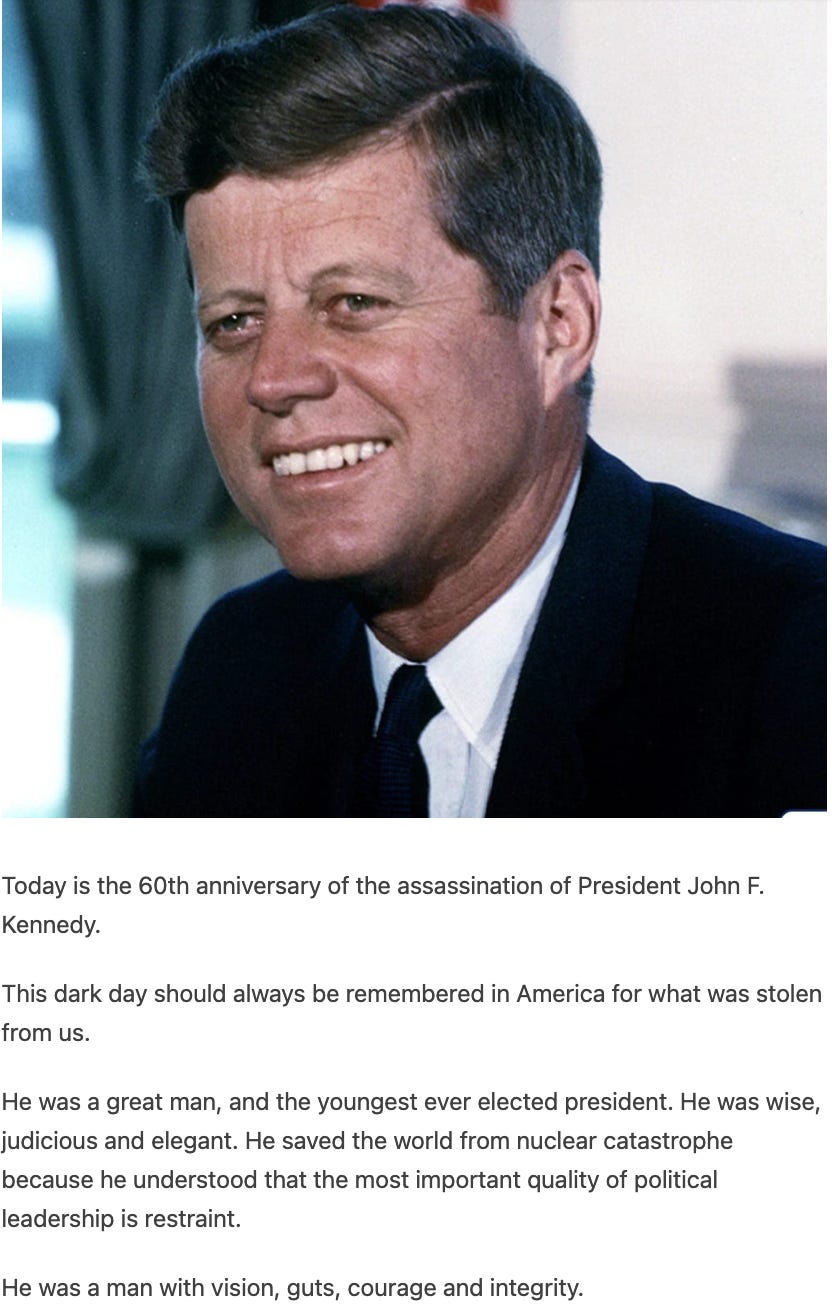

Today marks the 60th anniversary of the assassination of John F. Kennedy, Jr. I’m at a bit of a loss as to what to say about that awful day, seeing as how I was all of three-and-a-half years old when it happened. But that day represents my first memory, and it’s stuck with me as if it happened yesterday.

Of course, the significance of what was happening was almost completely lost on someone as young as I was, though I knew something terrible had happened.

I remember one of my parents parking me in front of a television, and the camera was focused on a building in the distance. I can recall a man with a somber and sonorous voice telling his audience that the building was Parkland Hospital in Dallas, Texas.

I, of course, had no idea what a hospital was, nor did I know what a “Dallas Texas” was. I stared at the television screen for what seemed like forever as the many adults around me were crying for reasons I couldn’t understand.

That’s all I remember of that day- the tears of the adults around me and the television camera fixed on Parkland Hospital in what I suspect was probably a pretty grainy black-and-white broadcast. I don’t remember anything of what the newscaster said, though I’m sure it was all about JFK’s assassination, the significance of which I was far too young to grasp.

I’ve spent a lot of time figuring out what it was about that day that conspired to make it my first memory. Perhaps it was the gravitas of the moment. Even though I was far too young to understand what was happening, I knew it was important and terrible. It would be some years before I could grasp the importance of the historical moment that became my first memory, but on that day, I knew it was something big.

Over the years, through high school and into college, I spent a lot of time studying the history of what happened on November 22, 1963. I’ve read many books, seen more documentaries and movies than I can remember, and listened to more conspiracy theories than I can keep straight.

From where I sit, I think the truth is pretty simple. I believe Lee Harvey Oswald shot JFK, and I believe he did it of his own volition. Over the years, too many people have overthought and overcomplicated things. This is a case where I think Occam’s Razor applies- the most straightforward answer is probably the truth.

I can understand the continued interest in JFK’s assassination, of course. A good mystery…or at least a crime with unanswered questions, begs for those questions to be answered.

It’s not unlike the D.B. Cooper case. Yes, Cooper jumped out of a jet with a suitcase full of $200,000 somewhere over the Pacific Northwest, never to be heard from again. Neither he nor the money was ever seen again. Sure, one wants to think that Cooper survived and is living the high life in a country with no extradition treaty. But the truth is undoubtedly far more mundane.

Cooper probably didn’t survive the jump. More than likely, he landed in remote and rugged territory, was killed by the impact, or starved soon after landing. Then, his body probably decayed or was picked clean. And the suitcase? It probably was torn to shreds by the impact of landing. The paper money wouldn’t have lasted long in the damp Pacific Northwest climate.

Some have said, and probably not inaccurately, that November 22, 1963, was the day America lost its innocence. Before then, the security of a President had always been a relatively easygoing consideration. Chief Executives could travel through cities- even where they weren’t popular- in open-air vehicles, just as JFK did on his fateful last trip.

It wasn’t long before the Secret Service became far more serious about the safety and security of American Presidents. The actual and metaphorical distance between Presidents and the American people would become more significant due to security considerations. It would become increasingly rare for Presidents to find themselves in large crowds as JFK did frequently, including on the day he died.

And, if Jackie Kennedy had gotten her way, there wouldn’t have been a trip to Dallas at all.

“I’LL HATE EVERY MINUTE OF IT,” Jacqueline Kennedy said, as she contemplated her upcoming visit to Texas with her husband. More foreboding words have never been spoken.

It was November 15, 1963, and the first lady was with her friend Robin Douglas-Home, the nephew of the new British prime minister, at the Kennedys’ country retreat near Middleburg, Virginia. It was a dazzling fall day, the air crisp and the leaves a palette of gold and red.

“But if he wants me there,” Jackie said of her husband, “then that’s all that matters. It’s a tiny sacrifice on my part for something that he feels is very important to him.”

That she agreed to go was remarkable. She had never been to Texas before—and since John F. Kennedy’s election in 1960, she hadn’t even been west of the Mississippi, generally confining her domestic travels to the usual Kennedy destinations: Palm Beach, Hyannis, Newport, and Manhattan, where the family maintained a swanky apartment on the 34th floor of the famed Carlyle Hotel.

Her decision to accompany her husband to Dallas stemmed from—in quite a twist—her friendship with the man who would, less than five years later, become her second husband: Aristotle Onassis.

Dallas disliked JFK intensely, and he knew it. He’d lost the city by 60,000 votes in 1960, leading JFK to say, “I don’t know why we do anything for Dallas.” Ironically, his trip to the city that so disliked him turned out to be the one that saw him murdered and cost America so much of its innocence.

The Kennedys left the White House on Thursday, November 21. Twenty-six hours later, during the frantic race to Parkland Memorial Hospital, Jackie would fling the now bloodied pink pillbox hat off her head, ripping out a tuft of her hair in the process. She never felt the pain.

But America soon would, and it would be changed in ways it couldn’t have imagined when Friday, November 22, 1963, dawned.

Being three-and-a-half, I had no way of knowing what was happening or what it would mean for my life or the future of America. What I did know and remember is that I had a very clear sense that something terrible but terribly important had occurred, and its impact continues to be felt.

The adults around me were devastated by something, and it seemed connected to why I’d been planted in front of the television that was focused on Parkland Hospital.

Wow. Sixty years ago today….

I was in eighth grade and I remember all the teachers around me crying. They canceled school and my mom and I sat glued to the TV for over a week. When we did get out, it was to go to a swim center on a Sunday morning, where, waiting for my dad to get out of the showers, I saw full on, the assassination of Lee Harvey Oswald. I was watching by myself in a lobby area. My oh my how we have crawled through so many terrible, uncertain times. Yours is the first reminder this day--thanks

I was in the first grade, when the principal came into the class room to inform "us", though mostly the teacher. I did not understand what I was being told, but I had never seen adults in such a state of helpless shock before. Hell, it had never occurred to me that adults could be so completely unmade, and by nothing more than a few words.

The only thing that shook me as much was watching live as the plane hit Tower Two.