SREBRENICA, Bosnia — The gravestones stretch for nearly a quarter mile — 7,000 Bosnian Muslim men and boys, slaughtered in a matter of days — but the region’s top politician says the coffins are empty. The local mayor has said some of the purported victims are still alive. The commander who led the massacre is portrayed as a hero on posters that periodically appear near the cemetery.

It’s been 26 years since the killings in Srebrenica, a genocide that broke Europe’s never-again vow and constituted the bloodiest period of this nation’s three-year war. Much of the world turned its attention away from the Balkans after the U.S.-brokered peace deal in 1995, and the subsequent trial at The Hague, which handed down war crime convictions and life sentences.

But a battle over reality is now pushing the country to a breaking point.

While most Americans are focused- and rightly so- on the war in Ukraine, there’s another war that has never left my mind. My time in the former Yugoslavia during the war there left and indelible imprint on me. I spent most of my time living and working in Pristina, Kosovo, about 240 miles away from Srebrenica, until about a year before the mass killings began. I worked for Mercy Corps, an NGO (non-governmental organization) headquartered here in Portland, on a contract paid for by the US Agency for International Development (USAID), an arm of the State Department.

I was never able to go into Bosnia. First, it just wasn’t a smart thing to do given the war going on. Second, I was under orders from USAID to steer clear of Bosnia. However, while visiting a Bosnian refugee camp in Croatia, I made it to within about 10 miles of the border. That was close enough for me; I was adventurous, but I wasn’t stupid.

I didn’t need to go into Bosnia to confirm what was happening in places like Sarajevo and other cities. Shortly before departing Portland for Zagreb, Croatia, the Serb irregulars encircling Sarajevo dropped a mortar shell into the city’s central market, killing 68 civilians and wounding approximately 200. So even before I left home, I learned that I was heading into something unpleasant and possibly dangerous.

Because of the market bombing in Sarajevo, USAID kept me in Zagreb for a month rather than letting me travel through Macedonia and into Kosovo. There was no way to know what the Serbs manning the Kosovo border checkpoints would do to a lone American traveling on a non-diplomatic passport.

So I remained in Croatia and traveled to villages along the front lines there. To say it was an education wouldn’t begin to do justice to what I saw and heard from Croatian civilians and soldiers. For someone who’d grown up in a place where violence meant a snowball fight, being in a war zone was a stark awakening to the dark realities of the world.

It wasn’t just the vast destruction, the mile after mile after destroyed villages. It wasn’t merely the scores of shiny new marble headstones in Zagreb’s massive Mirogoj cemetery. It seemed as if each of those headstones represented someone under the age of 25 who’d been killed defending their country and before they’d had a chance to experience anything of life.

It wasn’t even the horrifying stories of rape and torture-or worse- I heard from noncombatants. No, it was the sense of dread and resignation that seemed to hang over Croatia, which at the time was relatively quiet.

Bosnia, however, was another story, as Serbs battled Croats in some parts of the country and Muslims in others. I heard rumblings of what was happening in Bosnia during my time in Croatia and Kosovo, which covered roughly the first six months of 1994. The genocide in Srebrenica occurred between July 11-22, 1995, and left, by one count, 8372 Muslim men dead.

Because it happened relatively recently, and because international investigators swooped in soon after, Srebrenica is one of the most thoroughly documented genocides in the world.

What investigators found was a crime scene that stretched for some 40 miles across eastern Bosnia, with its epicenter in Srebrenica, a mining town that had become a gathering point for some 40,000 Bosnian Muslim refugees during the war. The United Nations had claimed the area was a safe zone, installing peacekeepers to keep the Bosnian Serb army at bay. But the army, commanded by “Butcher of Bosnia” Ratko Mladic, showed up anyway and took control with ease. Serb officers separated the women from the men and boys. “Just don’t panic,” Mladic told the crowd. In fact, the men and boys were being taken to execution sites. People who tried to escape were gunned down by tanks and machine guns.

The bodies were initially buried in mass graves. But weeks later, as it became clear the war might end, they were exhumed and dumped in sites even more remote. The forensic analysts who arrived in the wake of the peace deal tended to find body parts rather than intact corpses, with remains of single individuals scattered across multiple sites. Sometimes bones had been fractured by excavators and bulldozers. Some of the gravesites were hidden away on the farmland of Bosnian Serbs. To this day, remains are occasionally found in the forest.

“These are not well-traveled roads,” said Matthew Holliday, the head of the International Commission on Missing Persons’ Western Balkan program, pointing to a map of gravesites — 95 and counting. “This was an effort to conceal.”

Because of the haphazard effort to conceal the bodies, efforts continue today- almost 27 years later- to identify victims as body parts are found. Some 7000 genocide victims are buried in Srebrenica’s cemetery, but more than 1000 people remain unidentified.

Complicating efforts to provide closure to families of victims are local Serbs who deny that genocide even happened.

This is a place where genocide survivors live right next to people who say it never happened — or that it wasn’t so bad. Denialism has long been an undercurrent of Bosnian politics and life. But in recent years, it has intensified, amplified by social media and by Bosnian Serb nationalist leader Milorad Dodik, who has called the massacre a “myth” and a “deception.” In July, a United Nations envoy intervened. Using extraordinary powers granted in the aftermath of the peace deal, he made genocide denial illegal in Bosnia.

That move has spurred a backlash — and fears of a violent dissolution.

Twenty-seven years later, there isn’t a day that goes by without me thinking of my time in the former Yugoslavia. I learned and saw things that I frankly wish I hadn’t, but it was part and parcel of my job responsibilities. I was surrounded by suffering and trauma I lack the words to adequately describe. Even all this time later, thinking about my time there evokes profound sadness.

I saw the best and the worst of humanity. I saw people working diligently to make a difference and alleviate suffering wherever and however they could. It was a drop in the metaphorical bucket, but to see kindness and selflessness in a place where suffering, death, and oppression were the order of the day restored my faith in humanity.

I was also surrounded by a Serb community that didn’t want me there and, if given half a chance, would’ve happily given me a cigarette and a blindfold and propped me up in front of a firing squad.

During my stay in Kosovo, I stayed with an Albanian family in the province’s capital of Pristina. An officer in the Serbian secret police and his family lived across the street. One day, as I was about to leave to walk to my office, he stopped me to say hello and make small talk. As I was about to say my goodbyes, he said, “You know, if war breaks out, I’m going to kill you and everyone in your house.”

The look in his eyes made it clear he wasn’t kidding and that he was quite capable of carrying out his promise.

The generalized Serb mindset- the world is against us and we must protect our own- was prevalent in Bosnia and used as justification for many of the atrocities visited upon Muslims and Croats.

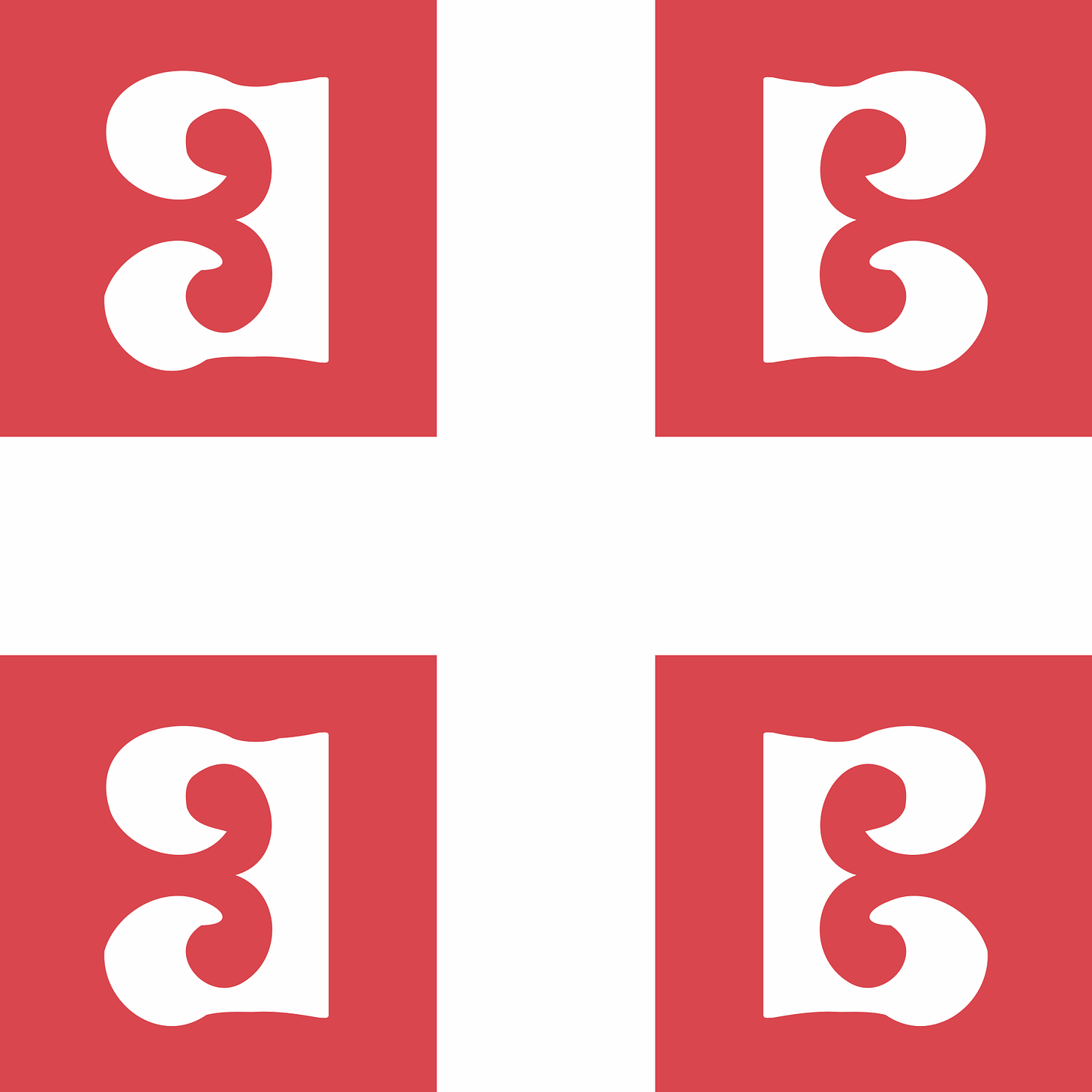

Само слога Србина спасава (Samo sloga Srbina spasava)- “Only unity will save the Serbs”- is a popular cry in Serbia. It’s used to rally Serbs against perceived foreign domination (paranoia is a profound hallmark of the Serbian national character) and during times of national crisis.

In Bosnia, the cause was the creation of a “Greater Serbia,” a place free of other ethnic groups and where Serbs could live safe from external threats. That achieving this goal meant engaging in what the world defined as “ethnic cleansing” was to many Serb ultranationalists merely a cost of doing business.

That mindsetdefines the current wave of denialise relating to the Srebrenica genocide. It does Serbs no good to focus on their ugly past, and so they whitewash it or deny it altogether as a way to avoid dealing with the consequences. If Serbs convince themselves that it never happened, that the accusations are coming from those out to get them, it gives them a common feeling of persecution to rally around.

That those consequences are still being felt by the families of those massacred almost 27 years ago should be enough for any compassionate human to believe that the work of identifying the dead needs to continue. Many Serbs, of course, have little interest in revisiting a past that reflects upon them harshly. And so they continue to deny the genocide a previous generation of Serbs are responsible for.

When bones are still turning up in the woods surrounding Srebrenica, it means the war isn’t over for the families of the victims yet to be identified. Whether or not Serbs care to acknowledge no longer matters. The Srebrenics genocide happened, and history will hold Serbs responsible for the atrocities committed.

The work must continue until all the victims are identified and laid to rest. It’s the least the international community can do. And no one, especially local Serbs, can be allowed to pretend that Srebrenica never happened.