Sometimes history has a way of disappearing from our collective memory. That’s a shame because it can cause us to forget things we need to remember. That memory can provide much-needed perspective, especially when tragedy strikes.

When Buffalo Bills safety Damar Hamlin collapsed on the field at Paycor Stadium in Cincinnati Monday night, the phrase we heard was variations of “nothing like this has ever happened before.” It was understandable that few alive today would recall anything like that moment, but it’s happened before. An NFL player HAS died on the playing field.

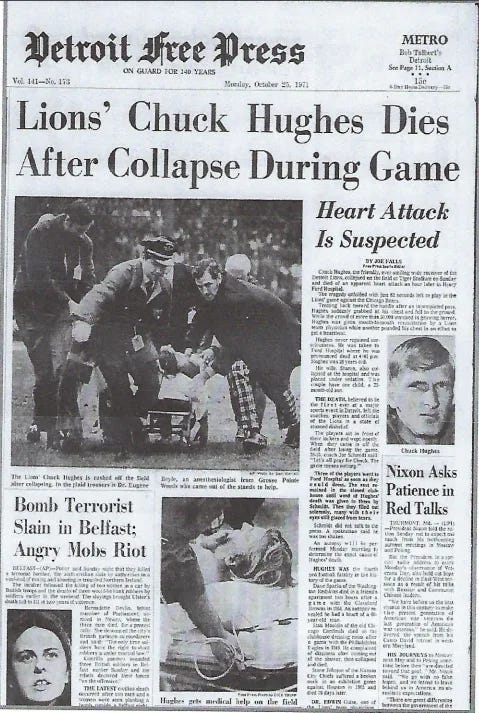

On October 24, 1971, the Detroit Lions were tied with the Minnesota Vikings for the lead in the NFC’s Central Division. Riding a four-game winning streak, the Lions were about the host the Chicago Bears at Tiger Stadium in front of 54,418 fans.

The game was blacked out on local television because, per NFL rules, it hadn’t sold out 72 hours before kickoff. Lions fans who weren’t at the game listened to the radio play-by-play of Van Patrick and Bob Reynolds on WJR-AM (760). Compared to the reach of today’s NFL, not many saw the game on TV.

By the end of the game, the result would seem meaningless.

Chuck Hughes was 28 years old that afternoon, a backup receiver for the Detroit Lions. On the surface he seemed as he was: an extraordinarily fit athlete, bulletproof, eager and willing to absorb the rough-and-tumble laws of NFL game days.

It was a mild afternoon in Detroit. The Bears, 3-2 on the season, had just taken a 28-23 lead on the 4-1 Lions in the fourth quarter. The Lions took possession. Larry Walton, one of Detroit’s starting receivers, busted up an ankle as the Lions tried to start a game-winning drive late in the game. Into the game trotted Chuck Hughes.

It was Hughes’ fifth year in the NFL. The Eagles had drafted him in the fourth round out of Texas-El Paso in 1967, and he’d caught six passes for a total of 68 yards in three years in Philadelphia. Traded to the Lions in 1970, he’d caught eight balls his first year as a Lion. Most of his time was spent on special teams. He’d yet to catch a ball in the ’71 season.

That changed immediately. Lions quarterback Greg Landry found Hughes for 32 yards, setting up the Lions at the Chicago 37-yard-line. The crowd started to stir. Hughes was clobbered on the play — tackled by two Bears defenders, one high, one low — but rose quickly and jogged back to the huddle.

Nothing seemed amiss. None of those assembled for the game- players, coaches, or fans- had noticed anything unusual. Indeed, Hughes was ready to go and in the huddle for the next play.

A couple of plays later, though, things turned for the worst.

Landry tried to hit tight end Charlie Sanders in the end zone but the pass was broken up. Hughes, serving as a decoy, had broken his route short at the 15-yard line. As he headed back to the huddle, his eyes locked briefly with Dick Butkus, the Bears’ fearsome middle linebacker.

A second later, those eyes rolled back in Hughes’ head.

He collapsed to the turf, clutching his chest.

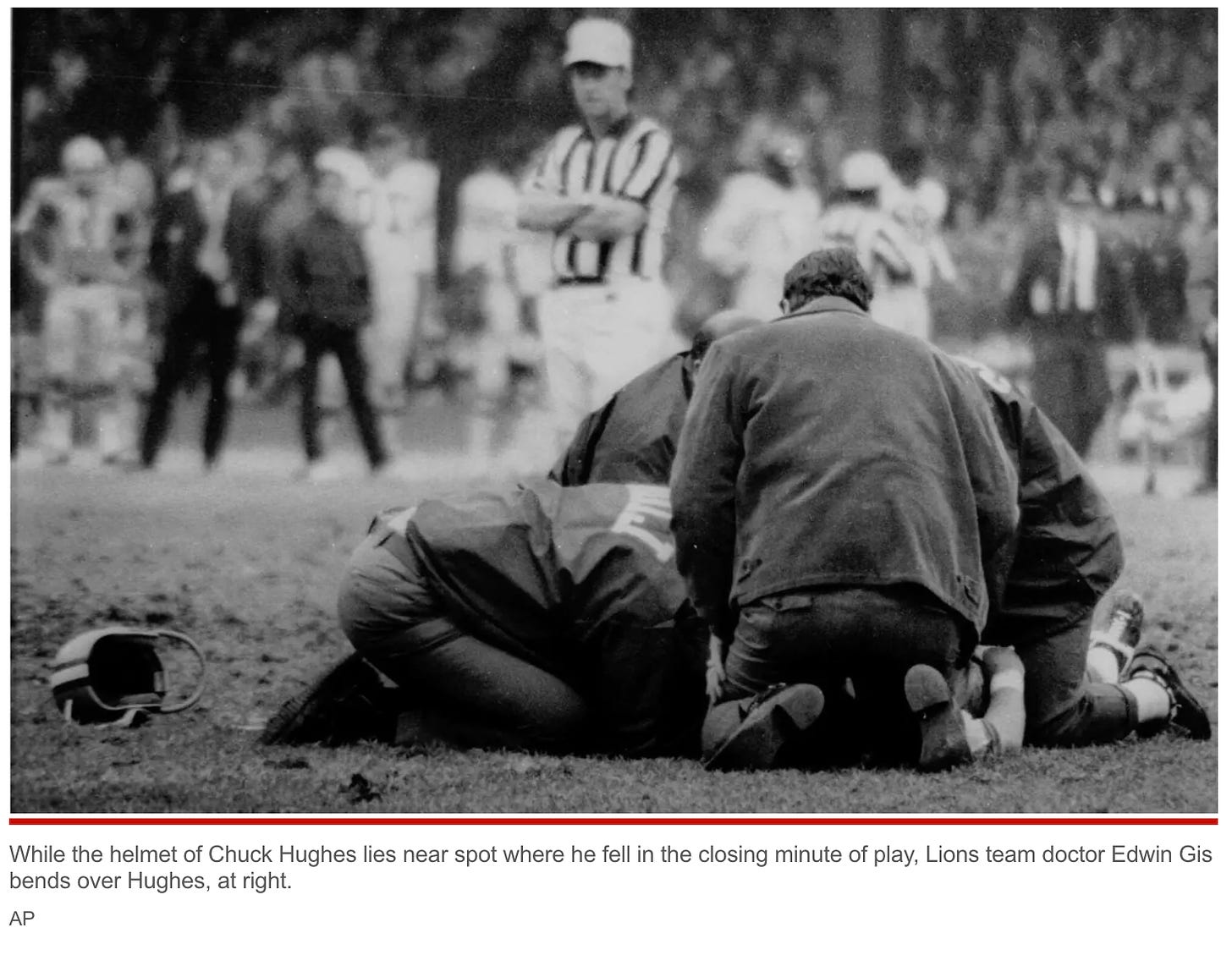

In the moment, the Bears thought he might have been faking an injury, which in those days was a not-uncommon practice. But it was Butkus who instantly realized this was no gamesmanship. He frantically began to wave for medical attention. Hughes’ arms were at his side, his helmet turned sideways. Trainers and doctors from both teams ran to Hughes’ side, as did an anesthesiologist who’d been attending the game as a fan.

There was 1:02 remaining in the fourth quarter. The Lions were running their two-minute drill and trying to get into position to score a touchdown. But after Chuck Hughes collapsed, none of the players cared about the remainder of the game. Chicago ran out the clock after quarterback Greg Landry threw an incomplete pass to Altie Taylor, and the Bears left with a 28-23 victory that no one gave a damn about.

Not all of the players initially realized what had happened, but Hughes was almost certainly dead before he hit the ground. And no amount of heroic effort would change that.

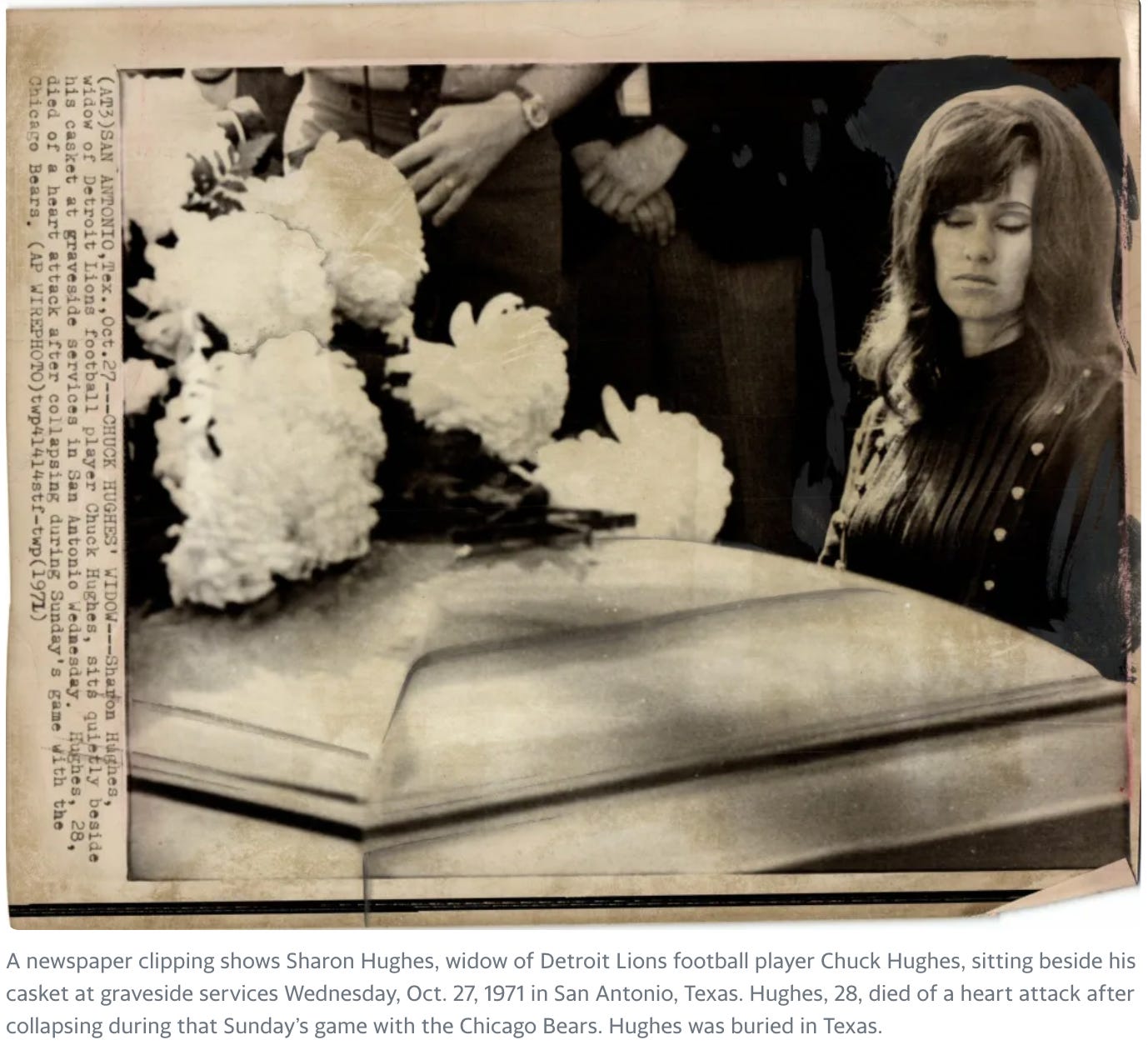

The following day the autopsy report revealed Hughes had died from an undiagnosed and advanced “arteriosclerotic coronary heart disease with acute coronary thrombotic occlusion” or as otherwise described by Thompson: "He had a hardening of the main artery supplying blood to the heart and a clot had formed in this artery shutting off the flow of a blood.”

The report also mentioned that there was old scarring on the posterior wall of the heart indicating evidence of previous heart trauma.

Guise told reporters, “One dies officially when one is pronounced dead, but in my heart, I feel Chuck died on the field.”

To this day, Falb agrees.

“We did everything we could based upon the skills and everything we knew at the time. You could have had the Cleveland Clinic and the Mayo Clinic on the field that day but he was not going to survive. He was dead,” says Falb.

Given the medical technology available in the early ‘70s, nothing would’ve saved Hughes, not when he was almost certainly dead by the time his body hit the field.

Today’s technology would probably have diagnosed his heart condition, and his life may have been preserved with medication and diet changes. Whether or not he would’ve been able to continue playing football would’ve been a decision for Hughes and his doctors, but it’s a moot point.

The critical point is that unlike what many pundits and commentators have stated, a situation like Damar Hamlin’s HAS happened before. And if Damar Hamlin had collapsed on the field in 1971, he probably would’ve suffered a fate not unlike that of Chuck Hughes.

Is this purely a “football problem?” Is the violence inherent in the game responsible for the death of Chuck Hughes? If you believe it is, then how do you account for the death of basketball player Hank Gathers? I’m not sure that football’s violence caused Hughes’ death, though one could convince me that it contributed.

Every sport has its risks. Some are more physically dangerous than others, and those who participate in them participate while fully aware of those risks. For example, I suffered seven concussions (that I can recall) over six months during my last season as a soccer goalkeeper. And yet I kept wanting to put on the gloves and go back between the posts and do what I loved to do. I was (sort of) aware of the risks, but I was willing to risk my future to play the game I love.

(This was back before much was known or much thought given to the long-term impacts of traumatic brain injuries (TBIs). There are still more questions that answers, and while I’ve probably suffered upwards of a dozen concussions in my life, I still feel like a test subject. There may be long-term consequences…but I just don’t know. Even my neurologist can’t tell me with any certainty.)

I did forego my last season of eligibility when it finally dawned on me that one more season of TBIs might leave me with the IQ of a cauliflower.

Athletes take risks; we accept that as part of the deal. Some take significant risks (football, hockey, soccer), and some take more minor risks (golf, track and field, cross-country), but we all make calculated decisions on what we’re willing to gamble with. To compete, we have to decide that our love of the game we’re playing outweighs whatever our fear may be.

Some enter into competition unaware that they have conditions that increase their risk and may unknowingly place their lives in peril. Chuck Hughes was one of those, and in 1971 it was probably harder to screen for such conditions. As a result, he assumed the risk of playing football and was felled by a disease he almost certainly never knew he had. The same may have happened to Damar Hamlin- or it may have been random blind lousy luck.

Whatever the case, Damar Hamlin is fortunate to have played football in 2022, a time when a tremendous amount of medical technology was readily and rapidly available when he went down. It now looks like he’ll survive- he was breathing on his own and even FaceTimed into a Bills team meeting yesterday.

I remember the day Chuck Hughes died. I’m not sure I was watching the game (I was 11), but I remember seeing a replay of him being stretchered off the field and hearing that he’d died of a heart attack. So when I heard Joe Buck say on Monday Night Football that this had never happened before, I immediately knew that was wrong. Perhaps it was a failure of institutional memory. After all, it was more than 51 years ago and thousands of games ago. The NFL has been fortunate that it’s been that long since a fatality has occurred, but I’m not sure that isn’t as much a product of good fortune as anything else.

Players have died on the basketball court- Hank Gathers- and on the ice- Bill Masterton. Drivers have been killed on the race track in numbers too large to list here. But, if we didn’t accept the risks inherent in the games people play, we’d be stuck watching the Professional Croquet Tour. Until someone decides to brain a competitor with a mallet, I suppose.

We should remember Chuck Hughes and others who’ve died in competition, even as we remember that no athletic pursuit is without risk. We can do what’s possible to make the games people play as safe as possible, but at some point, we must recognize that part of competition's appeal is physical conflict. And where there’s physical conflict, sometimes competitors can get hurt- or worse. Occasionally those injuries can be pretty serious, but those who compete accept those risks as part of the equation.

I still wrestle with the violence that’s the basis of the game of football. Some have argued that it’s time to ban football because of the violence, but things have been far worse. One need only hearken back to the turn of the 20th century when America’s gridirons were killing fields, and Theodore Roosevelt saved football from being banned. The game was brutal, and Roosevelt, who believed football helped to develop young men, was instrumental in developing rules to make it less savage.

Where football is today is not where it was 125 years ago, and Damar Hamlin’s injury was almost certainly a freak occurrence and not due to the game's violence. It was a football play, but not an unusually violent one.

Let’s not overreact based on one unfortunate incident. Football will always be, in the words of George Will, “Violence punctuated by committee meetings.” To be a player or a fan means making peace with that. Of course, there’s always the professional cornhole tour if you can't do that.