America should celebrate the release of Brittney Griner from her unjust imprisonment in Russia. It’s a just result for Griner, her family, and those who love her, and that’s certainly something worth being thankful for. Unfortunately, she was wrongly detained for more than nine months in conditions most of us can’t begin to imagine.

For her sake, I hope that her integration into freedom and her old life will be relatively smooth and that she’ll get whatever help she needs. Whatever the future holds for Brittney Griner, I hope that her experience in Russia won’t leave her irreparably damaged.

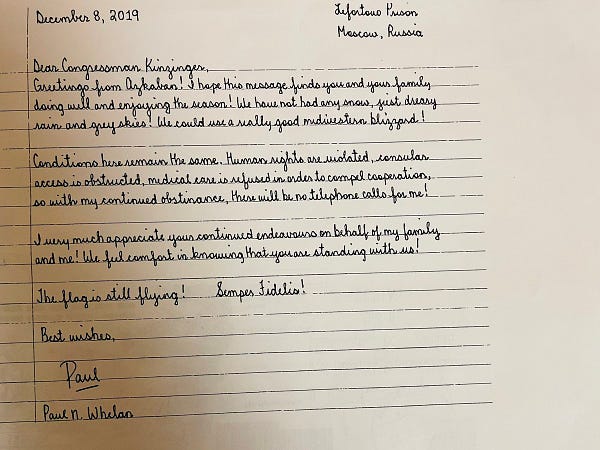

We should keep in mind that Griner was not the lone American prisoner in Russian custody, only the most renowned. Paul Whelan was arrested in a Moscow hotel four years ago and accused of espionage. The US State Department tried to arrange a swap that included Whelan, but the Russians refused. So rather than scuttle the deal they were after, the State Dept. took the deal they could get. It was bitterly disappointing for Whelan’s family, but they were exceptionally gracious in what had to be yet another devastating setback.

This episode reminded me of something I took very seriously when traveling outside the US. The world often isn’t a safe place to be American, and there are places where carrying an American passport may imperil your safety and well-being.

I’m not a paranoid traveler, but there are places where I’m very aware of what’s happening around me. There are also places where I feel on edge. In the mid-80s, it was traveling through the Middle East, particularly in Syria. No one had mobile phones then, and communication in Syria was no simple matter. There were parts of the country where, if you happened to “disappear,” it was conceivable that no one might know for days, perhaps even weeks. By that time, who knows what might have happened to you (or where your body might have been dumped)?

Somehow I always ended up more or less “in charge” of our security when traveling in Syria. It might have been my military background or that I was the largest one in the group and therefore looked the most “menacing.” Yeah, at 6’ and 200 lbs., I was barely a threat to myself, much less a Syrian militiaman wielding an AK-47.

There were certain things we could do to at least make it a wee bit more difficult for someone harboring bad intent to distinguish us as Americans. I made certain no one wore clothing with American logos- especially American colleges, universities, or sports teams. And no baseball caps; at that time, the only people in Europe or the Middle East who wore baseball caps were Americans.

If someone I didn’t know asked me where I was from, I answered that I was Canadian. It was easy enough; I grew up about 100 miles south of the US-Canada border and had spent enough time north of it to fake it. Plus, being a huge hockey fan helped. I still had enough of my Minnesota accent left that I could pass for being from south of Winnipeg.

In Syria, up until the civil war, one had to be extremely careful about who one spoke to as well as the topics of conversation. The secret police, loyal to Hafez Assad and then his son, Bashar, were embedded in virtually all aspects of life, and most Syrians were terrified of them. As tourists, one could just as easily endanger a civilian as yourself, so caution was a 24/7 priority. In this case, paranoia was good because it kept you on your toes.

I was a wet-behind-the-ears 24-year-old kid, and this was my first experience running into just how dangerous the world outside our borders can be. When I first traveled to Syria, a friend cautioned me- “Remember, being an American doesn’t count for shit there. Stay in a group, don’t go into places that look like they might be off the beaten path unless you’re with a guide, and don’t drink anything but bottled water.”

The advice about the water was brilliant. Unfortunately, we all got “Assad’s Revenge,” but we were able to delay it as long as possible. I remember laying on my bed in our $5/night hotel room in Aleppo, watching a cockroach climbing the wall and wishing someone would step on me. Fortunately, it was only a 24-hour inconvenience.

As I staggered out of my hotel room the following day, my face a light shade of green, I realized that whatever happened in Aleppo, no one would be riding to my rescue- no embassy, no consulate, no mommy, and no daddy. For the first time in my life, I realized how alone and on my own I was. That didn’t frighten me, but it was a very odd thing to learn and an unusual place to have such an epiphany.

(As it turned out, Aleppo would become one of my favorite places in the world. Then the civil war came along in 2011, and a good part of the city was leveled. It broke my heart. I still remember standing on the city’s citadel, looking north towards Turkey and wondering how many conquering armies had attempted to lay waste to Aleppo. Now, most of it has been turned to rubble, and it looks nothing like the city I fell in love with.)

It was then that it fully hit me that the world can be perilous and that “being an American doesn’t count for shit.” Indeed, there are some places where being an American might make you worth more- as a hostage.

When I was teaching in Cyprus, the civil war in Lebanon was running at full bore. I had several students who wanted me to come to Beirut to visit their families. They assured me their families would guarantee my safety, and I had no doubt they meant it. Unfortunately, that was also around the same time Lebanese militias were snatching Americans off the streets of Beirut.

I thought about the invitations for some time, but in the end, I decided I had no desire to become the next Terry Anderson or the next sacrifice for Allah. Discretion became the better part of valor. As much as I wanted to see Beirut (I still do), I decided that inserting myself in the middle of a civil war involving multiple militias probably wasn’t the wisest move.

Part of me wishes I’d gone anyway.

Two years ago, Erin and I were planning a trip to Finland, Latvia, Lithuania, Estonia, and Russia. This was just as COVID-19 was getting wound up, and just as we began to seriously consider an itinerary, Russia became the hot spot du jour. It became clear pretty quickly that a trip to that part of the world (this was before vaccines were available) wasn’t a good option if we wanted to continue living- which, in fact, we very much did.

Russia has always been on my bucket list, but I fear that now it will never happen, and with good reason. It didn’t take Brittney Griner and Paul Whelan to convince me that Russia isn’t a safe place for Americans. That’s been clear to me for a while now, and as much as I want to go, I wouldn’t subject Erin to the sorts of risks we’d face there.

I feel the most uneasy now in Mexico, primarily because of the situation with the drug cartels. It’s difficult for an outsider to understand what side the police are on, who’s armed, who’ll they shoot, and why. I’ve never had anything happen during my travels in Mexico, but neither have I felt exceptionally comfortable. And I’ve had to deal with hung-over and decidedly trigger-happy Serbian paramilitaries and police officers.

We certainly have problems within our borders, but at least we understand them, and they (mostly) speak English. Once we leave the relative safety of the US, however, the rules we’re used to operating under no longer apply. Many American travelers never seem to understand that American laws don’t follow them overseas. They can’t grasp that being an American “ain’t worth shit” in some places.

Once you’re in a foreign country, though, not only do the customs of that country apply but so do the laws- and sometimes those laws and customs don’t make a lot of sense. But, they weren’t designed to make sense to the American way of thinking.

Remember this when you’re traveling because when you’re outside the loving arms of America, the world can look a whole lot different.

And sometimes a lot more dangerous.

The State Department website actually says (about Russia): get out now. We can’t guarantee your safety. It’s bone chilling.

I live 100 miles from the Canadian border, in central New York. For many of the reasons you've espoused in this post, YEARS ago, I bought Canadian flag patches for the backpacks my wife and I carry while traveling. Happy trails, eh?