They're Human Beings, Not Machines

Workers can be pushed only so far before they push back...and no one wins when that happens

Post-COVID, it seems many industries are pushing workers harder, asking more of them- in some cases, because there are fewer of them to handle the same workload. But while workers are continually asked to do more with less, seldom are working conditions or compensation improved. Instead, workers are expected to suck it up, work smarter, and not complain.

Some employers have yet to figure out that it’s not a buyer’s market.

Business owners and managers don’t seem to understand that people have limits and that many workers were at their limits before the pandemic. Once they returned to work and found new and increased expectations, it pushed many over the edge. After that, they had nothing more to give.

This is the fourth time Kelley Anaas, an ICU nurse, has gone on strike. She’s worked at the same hospital for 14 years but now, “this job has to get better or I have to leave,” Anaas told Jezebel from the picket line. “As hard as it is and how defeated I feel at the end of every shift…I can’t do it for the rest of my career.”

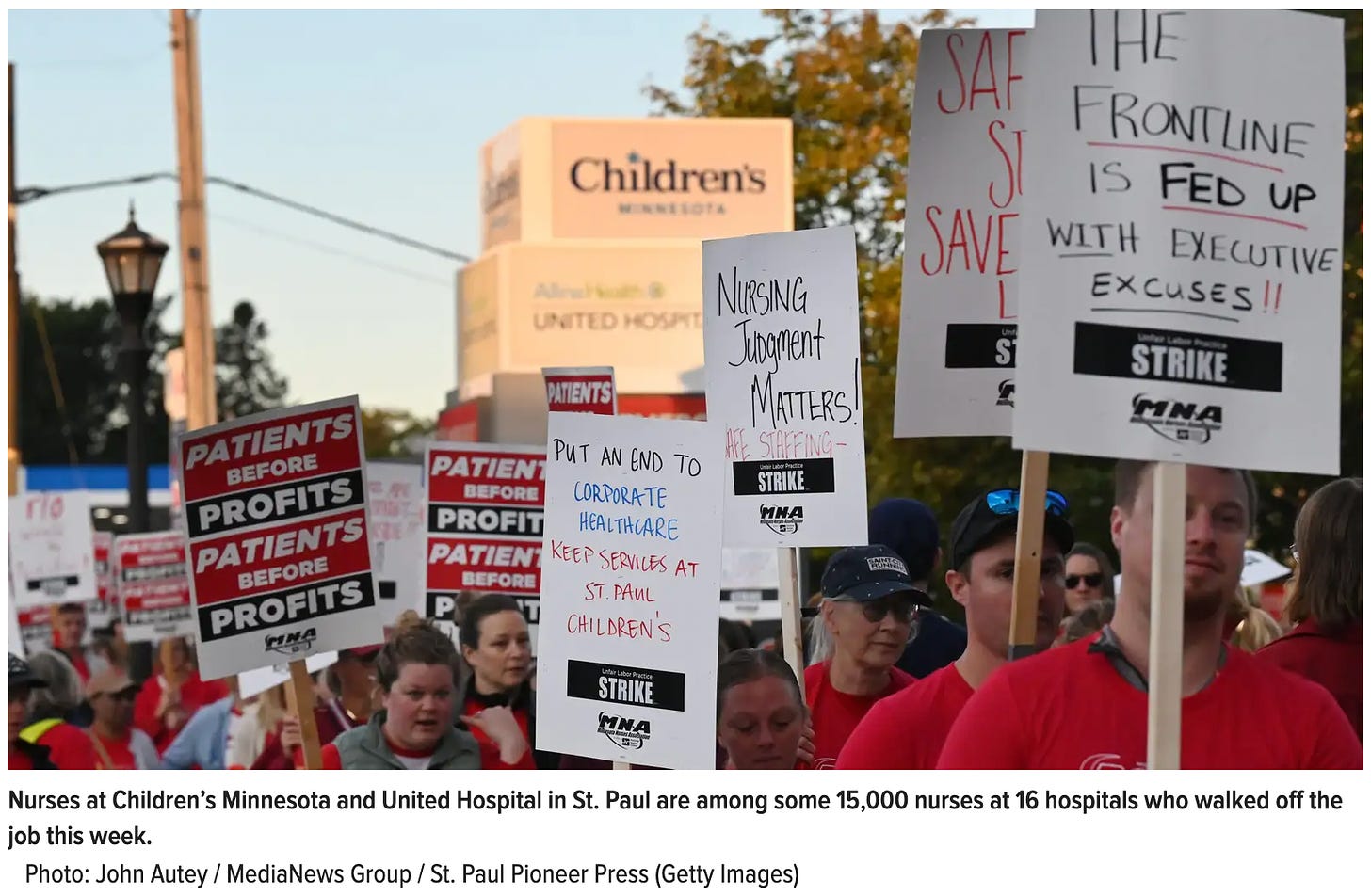

Anaas is one of 15,000 nurses in Minnesota who walked off the job for three days this week. It’s the largest strike of private nurses in American history. The workers want the hospital to prioritize hiring local nurses, instead of relaying on agencies and travel nurses to fill staffing shortages. They also want paid family leave and safety policies implemented, both regarding guaranteed PPE as well as paid leave for assaulted staff members. “I would love to do this for the rest of my career, but it’s been physically, mentally and emotionally damaging,” Anaas, who’s head of her chapter of the Minnesota Nurses Association, said. “It’s not sustainable what we’re being asked to do.”

It’s a problem that exists not only in Minnesota but across the country. My wife works in a hospital that employs traveling nurses to fill staffing shortages. Travelers make significantly more money than local staff, which creates resentment among those making far less for doing the same work.

Healthcare isn’t the only industry struggling with the realities of how to do business in a post-pandemic world. It is one of the most important, however.

These nurses are part of yet another industry pushed to the brink by the pandemic, demanding employers, and the country’s tenuous economic outlook. Freight railroad workers nationwide are threatening to strike on Friday over attendance policies that promote unsafe working conditions. On Tuesday, Seattle teachers voted to suspend their five-day strike, pending a successful contract ratification. In Michigan, faculty at one university walked off the job for five days, ending on Sunday, and one hospital system’s nurses (who have been without a union contract since July) authorized a walkout two weeks ago. Nurses in Wisconsin only didn’t strike this week because the governor was able to broker a last-minute deal. Nearly 700 nursing home workers in Pennsylvania were on strike for seven days following Labor Day. Not to mention the United Mine Workers of America who have been on strike for 16 months in Alabama.

It’s been a long year of organized labor speaking out about working conditions and demanding more.

Nurses in Minnesota limited their 15,000 members to a three-day strike to limit their time away from patient care while making their voices heard. Their message is clear: If you take care of your nurses, patients also benefit. Anyone who’s spent any time at all in a hospital knows that nurses are what keep the place running. Take the nurses out of the equation, and what you have left is chaos on a large scale.

Again, healthcare is one example of organized labor standing up and saying enough is enough. Most of the strikes taking place are necessarily about money being the top priority. But many also involve working conditions- vacation time, sick pay, retirement pay, etc. It’s about making employees feel as if their employers give a damn about them, that there’s a commitment to the well-being of those who work for them. In too many cases, that feeling isn’t there, which can lead to morale problems, staff attrition, more morale problems, more staff attrition- one leads to the other, and before you know it, your job sucks.

I listen to Erin frequently express her frustration about the state of healthcare. It’s become less about patient care and more about dollars and cents. Patient care, while still important, has taken a back seat to business, and the bean counters in far-off corner offices determine much of what happens. And if there’s one thing I’ve learned in the years I’ve known Erin, it’s that medicine and business seldom mix well.

Other industries have similar concerns that inevitably trickle down to workers, who are expected to cope with the fallout without being given additional space to incorporate additional expectations into their daily responsibilities. And when those responsibilities continue to expand…well, you can only stuff eight pounds into a five-pound sack for so long before something gives way.

Executives can’t continue to expect more from fewer workers without providing something in return. Working smarter is all well and good, but while squeezing more out of workers may be great for a company’s bottom line, it does little for the workers getting squeezed. Until companies acknowledge the additional stress and strain their workers are under, they’ll face more actions by organized labor- up to and including strikes.

You can’t get more from workers already giving you everything they can. People can give only so much before they push back- or quit. Employers need to recognize what they’re asking of their workers before those workers make it clear that enough is far too much.

President Biden may have been able to help prevent a nationwide rail strike, but what happens when another vital industry reaches its breaking point? How long can the President be expected to keep plugging holes in the dike?

It’s time for businesses to recognize that workers are commodities to be squeezed until they’re no longer of value. They’re people who care and want to work hard and who expect to be cared for and treated with respect and decency in return.

That shouldn’t be too much to ask…should it?