"How can I make things better for as many people as possible?"

Bill Walton (1952-2024) may have been a great basketball player, but he was an even better person

I never met Bill Walton, though I wish I’d had the privilege. As a young kid in northern Minnesota, I knew of him early in my basketball life. I wanted to be him, though he had almost two feet and more game than I could dream of on me.

I didn’t fantasize about hockey like many kids my age in that part of the country. I was a gym rat. Any time the high school gym was open, I was there, and the sound of bouncing basketballs on a hardwood floor reverberating off of painted concrete walls still tugs at my heart.

I loved everything about basketball. I lived and breathed my own game, and I was addicted to hoops in all its forms, whether it was high school, college, the NBA, or the Olympics. One of the darkest days of my youth was the 1972 Olympic Gold Medal game when the international officials finally succeeded in giving the game (and, with it, the gold medal) to the USSR. To this day, the Americans on that team have refused to claim their silver medals.

Ah, but I digress.

One of the college games I’d most eagerly looked forward to was the 1973 NCAA Men’s Championship game between UCLA and Memphis State. Unfortunately, my parents had a hard and fast rule regarding my bedtime, and the game tipped off after I was supposed to be in bed. So, no game for Jack—at least insofar as Mom and Dad said.

There was an air-flow grate between the upstairs and downstairs in our house, so I lay on the floor with my ear to that grate and listened to the game instead of going to bed. I listened quietly as Bill Walton scored 44 points to lead UCLA to the NCAA championship that night. I couldn’t see the game, but I pretended I was listening to the radio broadcast, which, in northern Minnesota, was the only way we could get a lot of sporting events.

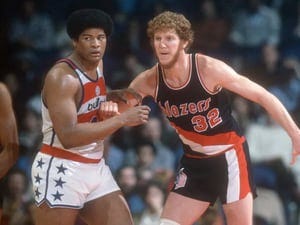

Walton was drafted first overall by the Portland Trailblazers, and after three frustrating, injury-filled seasons, led the Blazers to their first and only NBA championship in 1977. The Rose City is STILL living off that triumph. For years, well into the ‘90s, you could buy VHS tapes of the series-clinching Game 6 victory over Philadelphia. Now, of course, all you need is the magic of YouTube.

But if all you knew about Bill Walton were the NBA Championship he won in Portland and the 1986 Championship he won with the Boston Celtics, you’d be nowhere near knowing the full measure of the man.

Walton left Portland angry with the Trailblazers’ front office, but he loved Portland, and the city loved him back. He didn’t return often, but he was welcomed like the Prodigal Son when he did. Decades later, even people who weren’t alive in 1977 remember what he brought to Portland.

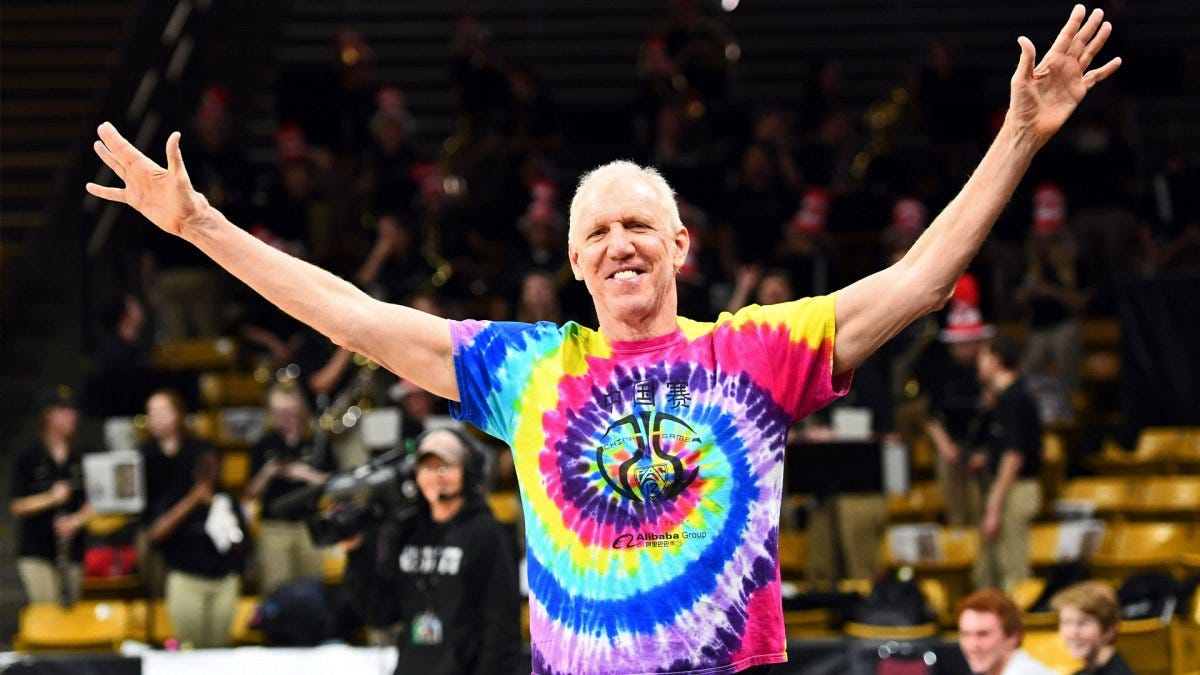

He was a two-time NBA champion. A seven-foot hippie with an eclectic personality and an unforgettable grin. Walton told me more than once that his mission in life was to leave the world better than he found it.

“Everything about my life is about making things better,” he said. “Better for the team.”

Better for UCLA. Then, the Trail Blazers. And the Boston Celtics. The world, too. You, me, and everyone else? Certainly his wife and children. We were all part of the world and by extension, Bill Walton’s team.

-

After basketball was over, Walton became even larger than life. He was the kind of person who’d ask you how things were for you and legitimately wanted to know. I saw one of his last interviews earlier this year and one of the things Walton said stuck with me. Walton talked about how he woke up every morning thinking about how he could make things better for everyone he encountered.

That wasn’t artificial. Walton wasn’t posing. He meant it and wanted to leave the people and places he encountered better than he found them. The gentle giant wanted to leave smiles behind when he left. Bill Walton was unconventional, particularly as a color man on basketball broadcasts. There were times when his commentary would stomp on game action, and you just wanted him to stop talking, and yet he could get away with it.

That was just who Bill Walton was—genuine, irrepressible, and prone to spreading happiness wherever he went and in whatever he did.

John Canzano’s story of Walton going to the Trailblazers' victory celebration is the stuff of legend, as if Walton were from another era—because he was.

Walton woke up the morning after that game at Lionel Hollins’ high-rise penthouse in downtown Portland. The center told me he hitchhiked back to his house, put on a fresh T-shirt, jumped on his bicycle, and rode it over the Broadway Bridge toward a sea of people at the victory celebration at Pioneer Courthouse Square.

Walton said: “It was like riding your bike into the Grateful Dead parking lot.”

You can gauge a person's impact by the volume and emotional depth of the comments made after their passing. It was easy to know that Bill Walton was loved and appreciated. Yes, he was a Hall of Fame player who cancer claimed far too soon at the age of 71. He should still be with us, spreading smiles wherever he travels, but the memories he leaves behind are still creating smiles even if those who knew him best are shedding tears over his passing.

ESPN did a documentary on Walton called “The Luckiest Guy in the World,” which, strictly speaking, was ironically hyperbolic. His basketball career was anything but lucky. One has to wonder what he could’ve been capable of had he not been hobbled by the myriad foot and ankle injuries that held him back. That he played in the NBA for 14 with two chronically bad feet is remarkable, bordering on miraculous—but out of those 14 seasons, his body allowed him to play the equivalent of perhaps five. That he did it in an era that lacked today’s medical technology makes his achievements even more incredible.

But those achievements came at a cost, including 34 surgeries that made walking painful and difficult after his playing days were over. But he could ride a bike, which he did often, participating in and leading rides, including here in Portland.

Over the last few years, he had been seen most often on basketball broadcasts, during which he was anything but your average color guy. He did and said Bill Walton things, but he was genuine, and no one else could’ve done what he did on TV.

To do that, though, he had to overcome a stutter. Later in his life, it would’ve been difficult to detect a trace of that handicap. And he never allowed it to hold him back. He was irrepressible, cheerful, and smiling until he was last seen in public.

And then, he was gone.

Bill Walton didn’t show up in Las Vegas at the Pac-12 Conference Tournament in March. We all suspected something was wrong. He wouldn’t have missed the final basketball event of the conference he loved so much.

Walton died on Monday surrounded by his family after an extended battle with cancer.

He was 71.

Where were you when you heard the news? I was in the garden with my 9-year-old daughter. We were putting a hibiscus plant in the ground. I was explaining that it needed sun, water, nutrients, and good soil. I glanced at a text.

“Bill Walton died,” a friend said.

It’s at quiet, unremarkable moments such as these when we realize how much someone means to us. Suddenly, a presence with us seemingly forever is gone, and there’s a hole in our hearts that they used to occupy, one we never thought we’d need to fill.

Bill Walton didn’t live in Portland, yet he was inextricably part of this community. I could feel it when I moved here 41 years ago. Whenever he came back for a visit, it was newsworthy. His problems were with the Trailblazers’ front office and their lack of trustworthiness, not with the city of Portland, which he loved to his last breath.

Walton leaves behind many broken hearts. This morning, I listened to an interview with ESPN’s Jay Bilas, who struggled to maintain his composure as he talked about one of his boyhood heroes. There are many more like Bilas out there.

This description can be a tired and seriously overused phrase, but in Bill Walton’s case, it’s true—we will not see his like again, and this world is poorer for it. Walton may have been a great basketball player, but he was an even better human being, and that’s humanity’s most significant loss.

Wherever centers go after they die, I hope his feet no longer ache. I hope he can run, jump, and dunk until his lungs are fit to burst. That will probably feel like Heaven to Bill Walton. He deserves nothing less.

All of my posts are public at this time. Any reader financial support will be greatly appreciated. There’s no paywall blocking access to my work (except for a few newsletters). I’ll trust my readers to determine if my work is worthy of their financial support and at what level. To those who do offer their support, thank you. It means more than you know.